God Made Serpents: Addressing Evolutionary Theodicy via Analogy of Being

They fought the heresy. They hated the heresy. They defeated the heresy. Millennia later, in a cave, a stranger uncovers the writings of the Gnostics. It became clear why the early Christians so reviled Gnosticism: some Gnostics maintained that the God who created this world was evil and imperfect. Early Christians defended the goodness of God despite the evil in the world. Were they wrong and the Gnostics right? Evolution would seem to indicate so. Evolution appears to leave little room for a good, let alone a perfectly good, God. Despite all the polemics, in the end, are the Gnostics vindicated? Or could a good, loving God employ evolution? Indeed, it will be argued, by analogy of being, God is not evil for creating with evolution. This will be demonstrated by, first, unpacking the problem of evolutionary theodicy, revealing how the primary problem is God intentionally inflicting suffering; second, defending the analogy of being argument and theology of nature; and finally, explicating genetic algorithms, showing, via analogy of being, that if humans are not evil for employing evolution then neither is God.

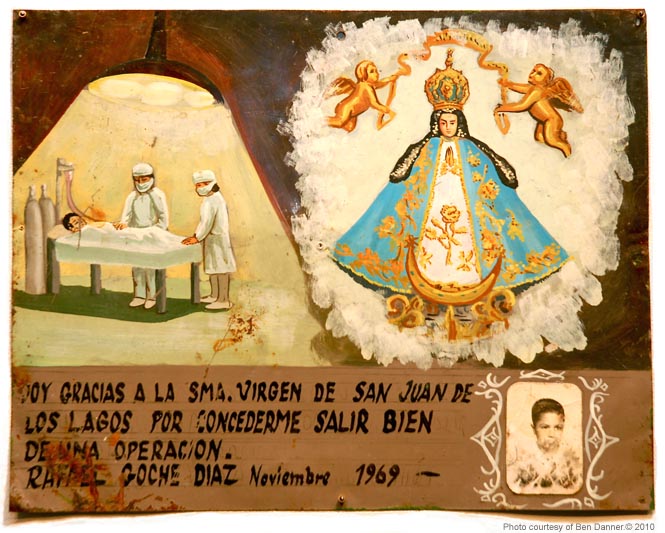

Boy Recovers From Operation, 13.5 x 10.5”, oil on tin.

Evolutionary Theodicy

Contrary to first impressions, the moral problem with evolution is far from clear. The randomness of mutations is not inherently evil. Randomness in general is not evil; if it were, the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics would be just as, if not more, evil than evolution.1 Nor is the problem death. All organisms must die, and if their death promotes evolutionary progress then it serves a long-term purpose. Some may argue evolution is wasteful, but then one assumes it is better to never exist than to exist and evolutionarily fail. This position exacerbates the problem by sentencing unsuccessful organisms to a fate worse than death: complete nonexistence. Pain is not the problem either, for it is necessary for interacting with the world: “…fear and pain clearly have their role. The burnt child fears the fire, and for good reason.”2 For Christopher Southgate, the problem of evolution “consists [in] the suffering of creatures and the extinction of species.”3 He argues that extinction is problematic becauseit “must be conceded always to be a loss of value to the biosphere as a whole.”4 Not only this, but extinction occurs frequently: 98% of all species that ever existed have become extinct.5 Southgate laments, “the evolutionary end of all creatures, as far as we can see, appears to be extinction.”6 However, extinction of species degrades a biosphere only if that species possessed superior adaptation(s). If one adaptation trumps another, it questions the value of the inferior adaptation. With natural selection, the superior species always wins, so the need to fret over a superior adaptation being lost is minimal: natural selection decides what is “superior” and preserves such adaptations.7

The remaining moral angst over evolution comes from suffering. Of course, “pain and misery exist in the animal world, whether Darwinism be true or not.”8 Even before Darwin, Philo, in David Hume’s Dialogues,observes, “the curious artifices of nature… embitter the life of every living being.”9 ,10 William Paley (also writing before Darwin) disagrees with this assessment: “through the whole of life, as it is diffused in nature, and as far as we are acquainted with it, looking to the average of sensations, the plurality and preponderancy is in favor of happiness by a vast excess.”11 Before evolutionary theory, one could legitimately debate whether or not nature promotes organisms’ well-being. A skeptic, like Philo, would comment that “every animal is surrounded with enemies which incessantly seek his misery and destruction.”12 However, a theist, like Paley, would reply, “at this moment, in every given moment of time, how many myriads of animals are eating their food, gratifying their appetites, ruminating in their holds, accomplishing their wishes, pursuing their pleasures, taking their pastimes?”13 Paley would remark, “happiness is the rule; misery the exception,”14 to which Philo would likely have countered, “if pain be less frequent than pleasure, it is infinitely more violent and durable.”15 And so the two would have danced forever if not for the intervention of Darwin. Clearly, evolution undermines this argument: nature operates “from processes in which there is no planning, no design, but only the operation of blind and simple rules.”16 Philo was right: “it seems enough for [nature’s] purpose, if such a rank be barely upheld in the universe, without any care or concern for the happiness of the members that compose it.”17 Evolution settles the debate as to whether nature is for creatures’ happiness or is utterly indifferent to them: indifference wins. So while evolution does not add to the suffering in nature, it renders null arguments that nature’s overall design is for happiness.

Further, evolution exacerbates the problem of suffering by making it nature’s very foundation.18 Evolution means “the way in which organisms were created and the way in which they function is one which necessarily entails a great deal of pain and suffering.”19 Nature is an indifferent zero-sum-like game: “it is a characteristic of nature that the full flourishing of some individuals is at the expense of that of other individuals, either of the same species or of others.”20 Southgate does not believe that one superior species emerging justifies the deaths of other species;21 in other words, the ends do not justify the means. The problem is still worse than that: not only do the ends not justify the means, but “the character of the creation is such that many individual creatures never ‘selve’ in any fulfilled way.”22 By creatures “selving,” Southgate means creatures living fulfilled lives.23 Evolution allows, and arguably even encourages, organisms to exploit the young of others, preventing selving and spreading suffering on a massive scale. The deaths of innocent, unselved creatures drive evolution, ensuring the weak do not reproduce and the strong do.24 Concomitantly, “since… the properties such as complexity and self-consciousness evolve by a process that denies full flourishing to a high proportion of the individuals and species that evolve, the long-term teleological problem in evolutionary theodicy is unavoidable.”25

Theodicy, of course, requires evil. Evil shall be defined as “intentional action to bring about unjust harm to one or more others.”26 Under such a definition, God can easily be construed as evil: God designed a system of nature where unjust harm abounds. Did God accidentally create such a system? Could God not foresee the suffering? Even if God’s ultimate purpose in creation is humanity, why use a method where so many lives suffer for millions of years before the goal is realized? As Philo famously wrote, “Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Whence then is evil?”27 Allowing that God designed a system of suffering but does not directly cause any being to suffer will not do: “The trouble is that the charge doesn’t go away when the action of the Creator is made more remote…. […] Indeed, if we imagine a human observer presiding over a miniaturized version of the whole show, peering down on his ‘creation,’ it is extremely hard to equip the face with a kindly expression.”28 Indeed, “the distinction between God allowing evil and creating evil is blurred.”29 Appeals to free will fail: “free will cannot explain away the agony of the child in distress from a genetic ailment, nor even is it of much help to the prey of the predator.”30 Kitcher adds, “the appeal to ‘mystery’ is always available – and always an abdication of the spirit of inquiry. For those who would reconcile God and Darwin, it’s hardly an acceptable resting place.”31 Without reinterpreting nature as ultimately benign, removing God from evolution, or appealing to free will or mystery, one must account for the fact that “the ‘casualties’ of evolution… have suffering imposed on them by God for the longer-term good of others.”32

What does evolution imply about God? Southgate asks the question poignantly: “if we believe God desired the development of such values—complexity, diversity, excellence of adaptation—then, again, the sufferers are means to God’s ends. What sort of God is that?”33 Several thinkers have an answer. David Hull responds:

Whatever the God implied by evolutionary theory and the data of natural selection may be like, he is not the Protestant God of waste not, want not. He is also not the loving God who cares about his productions. He is not even the awful God pictured in the Book of Job. The God of the Galapagos is careless, wasteful, indifferent, almost diabolical. He is certainly not he sort of God to whom anyone would be inclined to pray.34

B. Jill Carroll suggests “to reclaim violent models of God is simply to be honest about the universe we live in and the cosmic, natural powers that seem to ‘brood and light’ within it.”35 Kitcher ponders, “if we search the creation for clues to the character of the Creator, a judgment of whimsy is a relatively kind one. For we easily might take life as it has been generated on our planet as the handiwork of a bungling, or a chillingly indifferent, god.”36 Ultimately, Kitcher sides with Richard Dawkins: “the universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.”37 That is, atheism is the best solution to the problem of evolutionary theodicy.

Defending “Analogy of Being”

One way out of evolutionary theodicy is to deny that evolution implies anything about God. Oppose all forms of natural theology, including analogy of being arguments, and evolutionary theodicy—with its implication that a good human would never create with evolution and therefore God is not good—disappears.

Karl Barth is one such theologian who opposes natural theology. In his dialogues with Emil Brunner, he defines natural theology as follows: “by ‘natural theology’ I mean every (positive or negative) formulation of a system which claims to be theological, i.e., to interpret divine revelation, whose subject, however, differs fundamentally from the revelation in Jesus Christ and whose method differs… from the exposition of Holy Scripture.”38 He vehemently criticizes: “I am convinced that as far as [natural theology] has existed and still exists, it owes its existence to a radical error.”39 For Barth, all knowledge of God comes from Scripture, and consequently natural theology provides superfluous knowledge at best, and idolatrous theology at worst: “if one occupies oneself with real theology [i.e., positive theology] one can pass by so-called natural theology only as one would pass by an abyss into which it is inadvisable to step if one does not want to fall.”40 Barth, in his Gifford Lectures, explains that he sees Reformation theology in complete opposition to natural theology; the two are mutually exclusive: “[Reformation theology] is the clear antithesis to that form of teaching which declares that man himself possesses the capacity and the power to inform himself about God, the world and man [i.e., ‘natural theology’].”41 Humanity on its own cannot discern any knowledge of God; humanity needs positive theology. Natural theology helplessly leaves humanity with a warped picture of God.42

Other theologians disagree with Barth’s assessment. For example, John Polkinghorne writes, “natural theology derives from the general exercise of reason and the inspection of the world. It is part of theology’s necessary engagement with the way things actually are.”43 In other words, all theologians must integrate their worldviews; theology should not promote cognitive dissonance. Barth believes sola gratia to be solely sufficient for theology.44 Here evolution creates a problem for theology: how does one integrate the scientific worldview with the Biblical worldview? Evolution all but eliminates any possibility of creation as paradise,45 a Garden of Eden, or the Fall. Barth may respond that original sin clouds science’s understanding of the world, but it is science’s understanding of the world that challenges the very idea of original sin. Even if sin distorts science’s perception of the world, where is the distortion in this specific case? Are evidences for evolution, such as the molecular clock, fossil record, and vestigial organs, a distortion of reality? Death is the reality of creation, and humanity’s appearance had no impact on this reality. God designed creation this way; what does this say about God? A theology refusing to engage with a scientific understanding of the world, hoping to find all the answers in the Bible, seems terribly disconnected from reality.

Perhaps Barth would not have responded to evolution by saying sin distorts scientific evidence, but that the realms of theology and science exist completely independent of each other.46 In a letter to his niece Christine, Barth writes, “Has no one explained to you in your seminar that one can as little compare the biblical creation story and a scientific theory like that of evolution as one can compare, shall we say, an organ and a vacuum cleaner—that there can be as little question of harmony between them as of contradiction?”47 However, to claim science has no impact on theology seems hard to sustain in light of evolution. Evolution directly impacts theology by precluding any literal interpretation of Genesis: the Earth’s age, natural history, and even modern anthropology contradict a literal reading of Genesis. Some theologians have adapted and read Genesis as metaphorical (which has been done at least since Origen), while others reject evolution and insist the Earth is 6,000 years old. That is, evolution splits theologians into young earth creationists and those who accept a long evolutionary history of life on earth. The theology of these two groups differs because of evolution. In fact, much of modern theology is a reaction to science and the Enlightenment in general (e.g., Schleiermacher, Hegel, Barth, Pannenberg, Polkinghorne). The total independence view ignores too much Christian history.

Even so, “natural theology” carries a troubled history. Instead, following Ian Barbour, a minimal “theology of nature”48 can be used to piece together the worlds described by theology and science.49 Here, “theology of nature” simply means that science speaks to the Creator’s relationship with the creation. Polkinghorne believes that theology “must have its anchorage in the way things actually are, and the way they happen.”50 A theology of nature admits that the Bible does not monopolize all the truths about God (even if everything it says about God is true): “the true Theist will be the first to listen to any credible communication of divine knowledge.”51 Brunner goes so far to argue that the Bible actually supports the idea of truth of God outside the Bible: “Scripture itself says so and upbraids man for not acknowledging it, and it expects from him as a believer that he should take part in this praise of God through his creation.”52 For Brunner, whatever impact sin may have on humanity’s perception of creation, it does not utterly hide or distort God’s workmanship.53

Naturally, Barth disagrees with Brunner’s interpretation of Scripture. Nonetheless, since holding that (1) the natural world says nothing about its Creator, (2) sin distorts humanity’s ability to observe the world, or (3) science and theology have no intersection all seem untenable, the next best argument would be to attack the analogy of being. Sin, it could be argued, so corrupts humanity that no analogy is possible between humans and God. Though a human using evolution to create life would be evil, no conclusion about God’s goodness can be drawn from this.

There are three possibilities concerning the truth of the analogy of being: (1) complete presence, if a human has attribute x, then God has attribute x; (2) complete absence, if a human has attribute x, God does not have attribute x; and (3) partial relation, if a human has attribute x and x has attribute y then God has attribute x. Complete presence is highly problematic. If a human acts in malice then so does God. If a human acts in benevolence then so does God. God acquires contrary attributes, making theology via negativa and via eminentia impossible. God cannot be said to not be something (e.g., not have limited knowledge) because all human attributes apply to God. Likewise, no single attribute of God can be uplifted via eminentia because God possesses all attributes. God is both all-loving and all-hating, pure justice and pure injustice. Technically, one could use via eminentia, but one would describe a self-contradictory God. Complete absence is equally problematic, for essentially the same reasons. If a human loves, God is not loving. Theology via negativa is impossible for the opposite of any human attribute is also a human attribute, leading to contradiction. For instance, if humans are hating then God is not hating but loving; however, loving is also a human attribute so God is not loving but hating, and so it loops forever. Theology via eminentia cannot even get off the ground, for there are no attributes of humans that mirror God. God is nothingness beyond nothingness: nothing conceivable or known to humanity can describe God. God as nothing directly opposes the idea of an Incarnate God who displayed God’s attributes in human form. Positive theology does not escape either, for it too wants to describe God as loving, merciful, just, etc., all of which can be human attributes. In turn, only partial relation remains for it is the only option that does not reduce theology to absurdity. God in Jesus Christ affirmed some attributes as God-like; God indeed shares some attributes with humans. Though sin may negatively alter humans’ attributes, it does not render all their attributes unGodly. The imago Dei partially remains.

Furthermore, analogies are essential to theology. Polkinghorne realizes that “attempts to articulate the knowledge of God will require language to be stretched by appeal to analogy.”54 Even Philo admits, “that the cause or causes of order in the universe probably bear some remote analogy to human intelligence.”55 Brunner argues such analogies imbue the Bible: “Man’s nature as imago Dei determines that he should not speak of God except by way of human metaphor. Father, Son, Spirit, Word – there all-important concepts of Christian theology, of the message of the Bible, are concepts derived from personality.”56 Without human analogy nothing can be said of God. As Cleanthes, one of Philo’s counterparts, observes: “if we abandon all human analogy… I am afraid we abandon all religion and retain no conception of the great object of our adoration. If we preserve human analogy, we must forever find it impossible to reconcile any mixture of evil in the universe with infinite attributes; much less can we ever prove the latter from the former.”57 The challenge in reconciling the Divine attributes with evil becomes even more difficult with evolution. A human using the suffering of many for the benefit of a few can be described as evil. God uses the suffering of many for the benefit of the few. Most Christian theologians do not want to attribute evil to God; rather, they want to uphold the qualities Jesus displayed as Divine and leave out evil qualities. In other words, they want to make attribute y goodness, but in the present case this seems impossible for they cannot envision a loving human creating through evolution: the two are mutually exclusive. When combined, evolution, analogy of being, and theology of nature appear to oppose God’s goodness. Without the ability to deny theology of nature or the analogy of being, theologians must seriously consider Kitcher’s point: “if we imagine a human observer presiding over a miniaturized version of [evolution], peering down on his ‘creation,’ it is extremely hard to equip the face with a kindly expression.”58

Genetic Algorithms

Kitcher cannot imagine a benevolent person using evolution. Actually, evolutionary programming, and genetic algorithms in particular, have gained prominence in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). Early AI researchers saw evolutionary algorithms as unnecessary: computer scientists would masterfully program their computers top-down to achieve machine learning. Perhaps not surprisingly, the first attempts failed, as robots, for example, committed foolish errors trying to navigate and manipulate the non-virtual world. In response, computer scientists devised more sophisticated algorithms to ensure the robot would behave more intelligently. Unfortunately, they did not anticipate the exponential increase in combinations this generated: rather than the robots behaving foolishly, they ceased to behave at all because they were too busy calculating “safe” maneuvers.59 Achieving AI would turn out to be much more difficult than imagined. The combinatorial explosion would have to be overcome bottom-up, not top-down. In other words, computer scientists cannot tell a robot everything it is supposed to know about its environment (top-down), but must program the robot so it can learn about its environment (bottom-up). One particularly successful bottom-up approach implements genetic algorithms.

Genetic algorithms employ evolution in order to find the best solution to a particular problem. They usually start either with some solutions the programmer assigns or with several randomly generated solutions. The algorithm then evaluates each solution in terms of fitness, i.e., how well it solves the problem. The algorithm selects the solutions best solving the problem, and terminates most (sometimes all) of the inferior solutions (the percentage of how many solutions survive in a generation of solution is usually fixed and dependent upon the problem). The surviving solutions crossbreed with each other, replacing the inferior solutions and thus restoring the original population of solutions. The new solutions are mutated, slightly altering how they solve. This new population repeats the process experienced by the initial population until either it finds a solution or a set number of iterations occur.60 ,61

Can a programmer who uses genetic algorithms be described as evil? Recall that the working definition of evil is “intentional action to bring about unjust harm to one or more others.” For sake of argument, allow “others” to include solutions and assume they suffer when they terminate. In this case, the answer seems to be “yes.” “But wait,” a programmer may object, “this is the only way to solve the problem. The intent of my action isn’t to bring about suffering at all but to solve the problem.”

Though one may be willing to believe a programmer’s only option is a genetic algorithm (i.e., evolution is the only way to effectively solve the problem), one may not be so willing to believe evolution is God’s only option. Surprisingly, Ruse cites Richard Dawkins to argue that evolution is indeed the only way to create life: “Dawkins… argues strenuously that selection and only selection can do the job. No one – and presumably this includes God – could have got adaptive complexity without going the route of natural selection. Why is this so? At least partly because adaptation and its complexity simply could not be produced by most putative evolutionary processes.”62 In order for life to be able to adapt to its environment it must be able to evolve. If no mechanism exists to adjust, then life perishes. Inevitably, having a natural law governing life may lead to problems when coupled with other laws of nature. Paley, though obviously not referring to evolution, recognizes natural laws can accumulate into “inconveniences:”

First, that important advantages may accrue to the universe from the order of nature proceeding according to general laws: secondly; that general laws, however well set and constituted, often thwart and cross one another: thirdly; that from these thwartings and crossings frequent particular inconveniences will arise: and fourthly; that it agrees with our observation to suppose, that some degree of these inconveniences takes place in the works of nature.63

Even God cannot make contradictory laws not contradict. The “forces that gave rise to earthquakes and other natural disasters are the very forces that made this biosphere possible,”64 and at the same time life needs to be able to survive in light of these forces. In other words, natural laws regulating a healthy biosphere must operate within certain bounds, causing natural disasters. If God created life statically, as the natural world ebbs and flows, all life, with no mechanism to evolve, would cease. God wisely chose natural laws to regulate life for without them there could be no sustained life. This means, as Ruse notes, “if God was to create through law, then it had to be through Darwinian law. There was no other choice.”65 Furthermore, the notion that God could create intelligent life top-down is computationally impossible. If God cannot make “1 +1 = 3” or other mathematical absurdities, then God also cannot prevent exponentially growing combinations (“combinatorial explosions”) because this involves defying the laws of combinatorics. Even God cannot solve problems requiring bottom-up solutions with top-down ones. “Surely God knows what ‘code’ the bottom-up solution would produce and can simply take that and implement it as a top-down solution,” someone may object. Perhaps, but even then from the program’s perspective it would appear as a bottom-up solution. That is, only the programmer would know that the solution was implemented top-down because to any other observer it appears bottom-up because it is a bottom-up solution. For intelligence, be it organic or robotic, that can successfully interact with an environment, evolution appears to be the only way.66 Ruse concurs: “in the case of organisms, there is no known physical rival to the slow, creative, adaptive-complexity-forming process of natural selection. So it is selection or nothing.”67 Therefore, the analogy of a computer programmer using genetic algorithms and God using evolution stands; both had to use evolution.

Philo disagrees: “None of them [evils] appear to human reason in the least degree necessary or unavoidable, nor can we suppose them such, without the utmost license of imagination.”68 He elaborates, comparing God to an architect:

The architect would in vain display his subtlety, and prove to you that, if this door or that window were altered, greater ills would ensue. What he says may be strictly true: The alteration of one particular, while the other parts of the building remain, may only augment the inconvenience. But still you would assert in general that, if the architect had had skill and good intentions, he might have formed such a plan of the whole, and might have adjusted the parts in such a manner as would have remedied all or most of these inconveniences. His ignorance, or even your won ignorance of such a plan, will never convince you of the impossibility of it.69

Polkinghorne defends the “only way” argument: “we all tend to think that had we been in charge of its creation, we would somehow have contrived it better, retaining the good and eliminating the bad. The more we understand the delicate web of cosmic process, in all its subtly interlocking character, the less likely it seems to me that this is in fact the case.”70 Still, no matter how improbable, Philo is right: ignorance does not entail the impossibility of anything; but ignorance cuts both ways: “since we cannot know if other universes might have contained less evil than this”71 one must confess an “agnostic cosmic theodicy.”72 No one knows if this is the best possible universe. Philo believes ignorance favors his position: “I will allow that pain or misery in man is compatible with infinite power and goodness in the Deity…. A mere possible compatibility is not sufficient. You must prove these pure, unmixed and uncontrollable attributes from the present mixed and confused phenomena, and from these alone.”73 While allowing for the compatibility between a good God and the present creation, Philo argues one must prove the former from the latter. However, as argued, if God created the universe with any major alterations, the universe would not have humanity as it is today: “to prevent natural evils from affecting man, man himself would have to be significantly changed such that he would be no longer a sentient creature of nature.”74 Since God had to create life using evolution and evolution does not “prove” a good God, one cannot argue that the universe must “prove” a good God. If such a universe existed, there would not be any intelligent creatures in it to ask such questions.

How, then, can the universe be understood? Philo offers four interpretations:

There may four hypotheses be framed concerning the first causes of the universe: that that are endowed with perfect goodness; that they have perfect malice; that they are opposite and have both goodness and malice; that they have neither goodness nor malice. Mixed phenomena can never prove the two former unmixed principles; and the uniformity and steadiness of general laws seem to oppose the third. The fourth, therefore, seems by far the most probable.”75

As already argued, the First Cause of the universe may be perfectly good and still have created the current universe. Philo’s overall point, that the universe is morally neutral, seems to contradict what the Bible teaches about the creation. No doubt natural selection, like gravity, is an indifferent, morally neutral process. Yet, this need not contradict the Bible. The Septuagint uses the Greek word kalos rather than agathos for “good.”76 In other words, the creation is aesthetically good rather than morally good. A good God created a beautiful universe. Darwin himself sees the kalos in the evolutionary process: “when I view all beings not as special creations, but as the lineal descendants of some few beings which lived long before the first bed of the Cambrian system was deposited, they seem to me to become ennobled.”77 From a computer programmer’s perspective, what really makes the universe kalos is the algorithm by which it was formed. Southgate concedes: “the nonhuman world possesses its beauty because of the processes that also involve the suffering associated with predation and parasitism and which engender extinction.” 78

Even if God could only create through evolution and evolution is aesthetically pleasing, one could object that the ends do not justify the means: “This may be the best possible world for the evolution of living things such as ourselves, and yet the question remains as to whether the creation of such a world is the activity of a good God. Other creatures… begin to seem no more than means to the divine end.”79 The analogy of a computer programmer only worsens the problem: the programmer cares not for each individual solution but only for the final solution – the one that solves the problem. In programming tic-tac-toe, this is the case since tic-tac-toe has a definitive solution. However, in another game, like chess, where perfect play is not currently known (i.e., it is unsolved), the programmer may delight in the incremental steps of the evolutionary process. An interested programmer would gladly check-in periodically and play with the chess program to relish in its progress. Ideally, a programmer would like to test each solution to better understand the effectiveness of the current generation of solutions, but this is not feasible. For God, who is presumably interested in the creation,80 delighting in each and every solution (organism) is possible. If God did not have a particular solution/organism in mind, but only a solution/organism with certain characteristics, then the current biological world can be analogized as a chess game. God could then watch in glee as life moves closer and closer to what God desires. Instead of the all or nothing “means to an end,” evolving life has value, albeit finite value, where the closer to the unreachable end goal, the more value a being has. Each solution/organism possesses inherent value and is much more than a means to an end. This analogy allows theologians to keep humanity at the top of God’s creation without disdaining the rest of creation. Of course, simply because God could delight in each step of evolution does not guard against the fact that God equally could not. The possibility of a deistic God has not been excluded. Some theologians prefer to guarantee against even the possibility of deism, but often at the cost of sacrificing omniscience, omnipotence, or both. Analogizing God as a programmer allows theologians to retain omniscience and omnipotence as traditionally conceived. To argue that the mere possibility of deism is enough to void an analogy that grants both omniscience and omnipotence overreacts. If this analogy excluded the possibility of a personal, loving God and only permitted deism, or even if it made deism much more likely, then resorting to voiding traditional divine attributes appears more palatable. However, since the possibility of a loving God cannot be excluded from this analogy and since this analogy preserves omniscience and omnipotence, it is difficult to see how just the possibility of deism is enough to mount a decisive objection.

Even if God could only create through evolution and evolution is aesthetically pleasing, one could object that the ends do not justify the means: “This may be the best possible world for the evolution of living things such as ourselves, and yet the question remains as to whether the creation of such a world is the activity of a good God. Other creatures… begin to seem no more than means to the divine end.”79 The analogy of a computer programmer only worsens the problem: the programmer cares not for each individual solution but only for the final solution – the one that solves the problem. In programming tic-tac-toe, this is the case since tic-tac-toe has a definitive solution. However, in another game, like chess, where perfect play is not currently known (i.e., it is unsolved), the programmer may delight in the incremental steps of the evolutionary process. An interested programmer would gladly check-in periodically and play with the chess program to relish in its progress. Ideally, a programmer would like to test each solution to better understand the effectiveness of the current generation of solutions, but this is not feasible. For God, who is presumably interested in the creation,80 delighting in each and every solution (organism) is possible. If God did not have a particular solution/organism in mind, but only a solution/organism with certain characteristics, then the current biological world can be analogized as a chess game. God could then watch in glee as life moves closer and closer to what God desires. Instead of the all or nothing “means to an end,” evolving life has value, albeit finite value, where the closer to the unreachable end goal, the more value a being has. Each solution/organism possesses inherent value and is much more than a means to an end. This analogy allows theologians to keep humanity at the top of God’s creation without disdaining the rest of creation. Of course, simply because God could delight in each step of evolution does not guard against the fact that God equally could not. The possibility of a deistic God has not been excluded. Some theologians prefer to guarantee against even the possibility of deism, but often at the cost of sacrificing omniscience, omnipotence, or both. Analogizing God as a programmer allows theologians to retain omniscience and omnipotence as traditionally conceived. To argue that the mere possibility of deism is enough to void an analogy that grants both omniscience and omnipotence overreacts. If this analogy excluded the possibility of a personal, loving God and only permitted deism, or even if it made deism much more likely, then resorting to voiding traditional divine attributes appears more palatable. However, since the possibility of a loving God cannot be excluded from this analogy and since this analogy preserves omniscience and omnipotence, it is difficult to see how just the possibility of deism is enough to mount a decisive objection.

Even granting that other organisms are more than a means to an end, Kitcher still resists the idea that the end (humanity) was worth the suffering: “when you consider the millions of years in which sentient creatures have suffered, the uncounted number of extended and agonizing deaths, it simply rings hollow to suppose that all this is needed so that, at the very tail end of history, our species can manifest the allegedly transcendent good of free and virtuous action.”81 Gregory of Nyssa disagrees: “Which, then, is better? Not to have brought our nature into being at all, since he knew in advance that the one to be created would stray from the good? Or, having brought him into being, to restore him by repentance, sick as he was, to his original grace?”82 That is, not only is God not evil for creating with evolution, but God is also good for redeeming creation. To argue it would be better for no life to exist at all than for life to exist in an evolutionary world is like arguing it is better for a handicapped child never to be born than experience a disadvantaged life. The parents of that child are more than “not evil,” and can be described as “good” for taking care of their disabled child. Extending the analogy of being argument, God is more than not evil but is good because of God’s redemption of humanity. What gets lost here is the fact that the critics try to shift the discussion from “is God evil?” to “should God have created at all?” Already, God cannot be labeled evil for God, like a computer programmer, did not intentionally act to bring about unjust suffering. The intentional act was quite innocuous—to bring about life! Suffering was a necessary side-effect. The initial act of creation can be good even if the creation itself is morally neutral.

Conclusion

As such, it has been argued, by analogy of being, that God is not evil for creating with evolution. This was demonstrated by, first, unpacking the problem of evolutionary theodicy, revealing how the primary problem is God deliberately causes suffering; second, defending the analogy of being argument and theology of nature; and finally, explicating genetic algorithms, showing, via analogy of being, that if humans are not evil for using genetic algorithms then neither is God. God used evolution to create life; the analogy of being argument is valid; humans use evolution (genetic algorithms); humans are not evil for using evolution; therefore, since humans are not evil for using evolution, via analogy of being, God is not evil for using evolution. This analogy holds because (1) in the cases of both God and humans evolution is the only solution, (2) no solution/organism must be a mere means to an end (no unjust suffering for the sake of others), and (3) the process itself is kalos. Darwin, not surprisingly, summarized evolution best:

Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.83

Endnotes

2 Karl Barth, The Knowledge of God and the Service of God According to the Teaching of the Reformation: Recalling the Scottish Confession of 1560, trans. J. L. M. Haire and Ian Henderson (London: Hodder and Stoughton Publishers, 1960), 5.

3Barth, Natural Theology: Comprising “Nature and Grace” by Professor Dr. Emil Brunner and the Reply “No!” by Dr. Karl Barth, 75.

4 Barth, The Knowledge of God and the Service of God According to the Teaching of the Reformation: Recalling the Scottish Confession of 1560, 8-9.

5 Barth, Natural Theology: Comprising “Nature and Grace” by Professor Dr. Emil Brunner and the Reply “No!” by Dr. Karl Barth, 82.

6 John Polkinghorne, The Faith of a Physicist: Reflections of a Bottom-Up Thinker (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 3.

7 Barth, Natural Theology: Comprising “Nature and Grace” by Professor Dr. Emil Brunner and the Reply “No!” by Dr. Karl Barth, 85.

8 Southgate, 5, puts it plainly: “there is no scientific evidence that the biological world was ever free of predation and violence.”

10 Karl Barth, “To Christine Barth, Zollikofen, near Bern,” from Letters 1961-1968, trans. Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981), 184.

11 See Ian G. Barbour, Religion and Science: Historical and Contemporary Issues (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997), 98ff, for more on his distinction between natural theology and theology of nature.

15 Emil Brunner, Natural Theology: Comprising “Nature and Grace” by Professor Dr. Emil Brunner and the Reply “No!” by Dr. Karl Barth, 24-25.

22 See, for example, James Lighthill, “Artificial Intelligence: A General Survey” (paper presented at the Science Research Council, 1973), for the problem of combinatorial explosions in AI.

23 For a technical description see John R. Koza, Genetic Programming: On the Programming of Computers by Means of Natural Selection (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2000), 17ff.

24 For example, suppose a programmer wants to write AI for tic-tac-toe. A programmer could design the AI to recognize and match pairs. “X” would mean the space is occupied by an “x,” likewise for “o,” and “#” would mean the space is unoccupied. So the starting state for tic-tac-toe would be (### ### ###): the first set of three symbols represent the first row of the tic-tac-toe board, the middle set the middle row, and the third set the last row. All the states of tic-tac-toe would be mapped to different solutions. So one solution may process (### ### ###, ### #x# ###), meaning given an empty board, move to the center square. Another solution may process (### ### ###, ##x ### ###), meaning given an empty board move to the upper right corner. Now suppose the initial population consists of 100 randomly generated solutions. There will be some poor moves (### xx# #oo, x## xx# #oo), and some good moves (xx# ### o#o, xxx ### o#o). All of the solutions would then be pitted against each other (perhaps exhausting every possible match-up, perhaps not), and then ranked according to win percentage. For simplicity’s sake, suppose only the top 10 solutions survive and the other 90 terminate. The remaining 10 solutions would then be crossbred, until the population once again totals 100. Crossbreeding can be done with one or more crossover point or randomly. A crossover point is where the solution will be spliced. Remember, all the solutions map all the possible states of tic-tac-toe to a particular move. To illustrate crossover points, suppose somewhere in solution A’s mapping sequence it reads (…(xo# oox ###, xo# oox #x#) (xox oox ###, xox oox #x#)…), and crossbreeds with solution B, who maps the same points as (…(xo# oox ###, xo# oox ##x) (xox oox ###, xox oox ##x)…). If the crossover point happens to be right in between the two combinations (xo# oox ###, …) and (xox oox ###, …) then one possible offspring, call it C, from A and B would have (…(xo# oox ###, xo# oox #x#) (xox oox ###, xox oox ##x)…) and another, call it D, (…(xo# oox ###, xo# oox ##x) (xox oox ###, xox oox #x#)…). Solution C takes the best from both parents while solution D takes the worst. Using two crossover points applies the same principle, only in two places rather than one. Random crossover means instead of using a fixed point, each pair is randomly selected from a parent. After the crossbreeding, each offspring undergoes mutation. Some (usually very few) aspects are tweaked. In solution D’s case, (xo# oox ###, xo# oox ##x) might be changed to (xo# oox ###, xo# oox x##). It is not terribly helpful, but it is a random change after all. Mutations will sometimes weaken good moves, but the variation it brings betters solutions in the long run, even if temporarily solutions take a step backward. Lastly, the new offspring joins the surviving 10 and the process repeats. In this case, since tic-tac-toe is solvable: the process will end when the AI plays perfect tic-tac-toe.

29 Some computer scientists theorize that using quantum computers could achieve similar results in a top-down fashion. It is readily admitted that if computer scientists can successfully program AI machines using a top-down approach, be it through quantum computers or otherwise, this argument collapses.

43 The point being argued is not that God necessarily is not evil, but that God can be construed as not evil. As such, this is a valid assumption.

45 Gregory of Nyssa, Christology of the Later Fathers, ed. and trans. Edward R. Hardy (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1977), 285. Granted, he is assuming original sin but his point that existence is better than nonexistence, especially if God saves, stands without the doctrine of original sin.

47 In fact, both Job and Ecclesiastes suggest that God deliberately uses chaos (randomness). Genesis suggests that God tames chaos, not that God defeats or obliterates it.

48 Michael Ruse, Can a Darwinian be a Christian?: The Relationship between Science and Religion (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 131.

49 Christopher Southgate, The Groaning of Creation: God, Evolution, and the Problem of Evil (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 9.

53 Granted, meteorites and other rare natural disasters have destroyed advantageous adaptations. The problem here, though, has nothing to do with natural selection or evolution but natural disasters. Actually, evolution makes recovery possible from such terrible natural disasters.

55 David Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1998), 59.

56 Southgate, 40, concurs: “the heart of the problem is that the experience of many individual living creatures seems to be all suffering and no richness.”

62 Philip Kitcher, Living with Darwin: Evolution, Design, and the Future of Faith (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 102.

70 Struck by this tragedy, Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (New York: Signet Classics, 2003), 87, seems to have felt obliged to offer condolence: “when we reflect on this struggle, we may console ourselves with the full belief, that the war of nature is not incessant, that no fear is felt, that death is generally prompt, and that the vigorous, the healthy, and the happy survive and multiply.”

72 A full discussion defining “evil” is outside the scope of this essay, but Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (New York: Benziger Brothers Inc., 1946), I-II.6, argues that “if the consequences follow by accident and seldom, then they do not increase the goodness or malice of the action: because we do not judge of a thing according to that which belongs to it by accident, but only according to that which belongs to it of itself….” In other words, intentionality is key to judging actions.