Human Uniqueness and Symbolization

The following is an excerpted chapter from van Huyssteen’s, Alone in the World? Human Uniqueness in Science and Theology. The Gifford Lectures, University of Edinburgh 2004(Wm. Eerdmans 2006)

The following is an excerpted chapter from van Huyssteen’s, Alone in the World? Human Uniqueness in Science and Theology. The Gifford Lectures, University of Edinburgh 2004(Wm. Eerdmans 2006)

Introduction

In earlier chapters my research into evolutionary epistemology (Chapter Two) and paleoanthropology (Chapter Four) yielded not only challenging, but also converging results on the issue of human uniqueness. It seems that both philosophically and scientifically it can be argued that the potential arose in the human mind to create art, to discover the need and ability for religious belief, to invent technologies, and – much later – to undertake science. In my second chapter I argued that what is distinctive about human beings is precisely this evolution of cognition, imagination, and religious awareness. This is the reason why one can argue that human behavior is only imperfectly understood if we do not take into account the very early emergence of religion, and then ask about the plausibility of religious and theological explanations for human nature as such. In an interdisciplinary conversation such as the one before us, theologians especially are challenged to take seriously the fact that our ability to respond religiously to ultimate questions through worship and prayer is indeed deeply embedded in our species’ symbolic, imaginative behavior, and in the cognitively fluid minds that make such behavior possible.

In the second chapter we also saw that the evolutionary epistemologist Franz Wuketits indeed argues that the need for metaphysics, and metaphysical explanations, seems to be a universal characteristic of all humans (cf. Wuketits 1990:117). In the fourth chapter on paleoanthropology we saw that even our earliest ancestors, the Cro-Magnons of the Upper Paleolithic, who were ‘us’ in every anatomical and behavioral way, seem to have had metaphysical systems or first religions, which almost certainly included notions about meaning, survival, beauty, life after death, and the ‘other world’. Evolutionary epistemologists explain the persistence of this kind of religious awareness as the result of the particular interactions between early humans and their external world, and thus as resulting from the specific life conditions in prehistoric times (cf. Wuketits 1990:118). This, however, raises two questions: why should we, so suddenly and only at this point, distrust the phylogenetic memories of our own direct ancestors, and should the emergence of religious consciousness only be explained in terms of specific life conditions in prehistoric times? Might there not be something about being human, something about the human condition itself, that could offer us a slightly different perspective on the enduring need for religious faith?

We also saw that an evolutionary epistemologist like Wuketits, after arguing for the propensity for religious belief in humans, and thus for the naturalness of religion, proceeds reductionistically to classify religious beliefs as giving rise to irrational world views (cf. Wuketits 1999:118). I argued in Chapter Two that this seems to conflict with his own careful distinction between biological and cultural evolution. Wuketits specifically argues, as we saw earlier, that there are indeed biological constraints on cultural evolution, but that culture is not reducible to biology. Cultural evolution, once started, obeys its own principles, giving the evolution of human cognition an entirely new and unprecedented direction (cf. Wuketits 1990:130f.). Wuketits does seem to be inconsistent, therefore, in using evolutionary arguments to curtail the scope of cultural evolution, interpreting all religious beliefs as irrational and determined solely by the way these beliefs are embedded in the way that our prehistoric ancestors coped with their worlds.

Against this background, theologian Tomáš Hančil was correct to use evolutionary epistemology’s own argument (‘instead of asking what kind of mind is required to know the world, we should rather ask what kind of world the world must be to have been able to produce the sort of minds we have’) to expose some of the reductionist and inconsistent anti-realist conclusions often singled out for religious world views only. What also became clear earlier is that a proper theological answer to this kind of reductionism can be very difficult indeed. Hančil was right to argue that this kind of scientism is only possible if one assumes that God does not influence our world in any meaningful way. Hančil was less successful, however, in his attempt to fuse evolutionary epistemology and theology by arguing that if God does influence the world, God’s influence should be part of the data that we work with (cf. Hančil 1999:240). I believe that evolutionary epistemology does challenge theology to take seriously the implications of the biological origins of human cognition and rationality, and of the embodied history of the evolution of this capacity. In the interdisciplinary conversation between theology and the sciences the boundaries between our disciplines and reasoning strategies are indeed porous, but that does not mean that deep theological convictions can be easily transferred to philosophy, or to science, to function as ‘data’ in a foreign system. In the same manner, transversal reasoning does not imply that scientific data, paradigms, or worldviews can be transported into theology to there set the agenda for theological reasoning. Transversal reasoning means that theology and science can indeed share concerns, can converge on commonly identified problems such as the problem of human uniqueness. We will see later that the argument from evolutionary epistemology, when transversally interwoven with the central paleoanthropological argument about human uniqueness, resonates critically with some core theological claims about human uniqueness. In addition I will argue, however, that precisely by also recognizing the limitations of interdisciplinarity, the disciplinary integrity of both theology and the sciences should to be protected. On this view the theologian can caution the scientist to recognize the reductionism of scientistic worldviews, even as the scientist can caution the theologian against constructing esoteric and imperialistic worldviews.

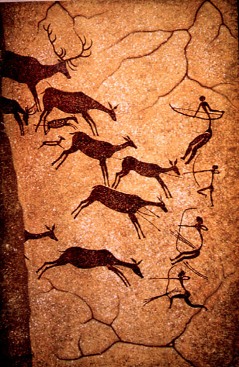

These mutually critical tasks presuppose, however, the richness of the transversal moment in which theology and paleoanthropology can indeed find a plausible interdisciplinary connection on the issue of human uniqueness. In Chapter Three I argued that the most responsible Christian theological way to look at human uniqueness requires, first of all, a move away from esoteric and baroquely abstract notions of human uniqueness, and second, a return to embodied notions of humanness where our embodied sexuality and moral awareness is tied directly to our embodied self-transcendence as believers who are in a relationship with God. In Chapter Four I argued that, from a paleoanthropological point of view, human uniqueness also emerges as a highly contextualized and embodied notion and is directly tied to the embodied, symbolizing minds of our prehistoric ancestors, as materially manifested in the spectacularly painted cave walls of the Upper Paleolithic. This not only opened up the possibility for converging arguments, from both evolutionary epistemology and paleoanthropology, for the presence of religious awareness in our earliest Cro-Magon ancestors, but also for the plausibility of the larger argument: since the very beginning of the emergence of Homo sapiens, the evolution of those characteristics that made humans uniquely different from even their closest sister species, i.e., characteristics like consciousness, language, symbolic minds and symbolic behavior, always included religious awareness and religious behavior.

In this chapter I now want to extend this argument and take a closer look at the symbolizing minds of our Cro-Magnon ancestors. First, I will ask about the role of culture and language in the evolution of symbolic and imaginative human behavior. A discussion of paleoculture will reveal adaptability and versatility as a remarkable human capacity in which the role of symbolic language was a crucial factor. This will reveal the prehistoric material ‘art’ from the Upper Paleolithic as exemplifying a profound dimension of imagination and symbolic meaning, in which the presence of spoken language has to be presupposed. In fact, the painting of images on cave walls could only have emerged in communities with shared systems of meaning, mediated through language. Second, I will focus on some of the current discussions in neuroscience and neuropsychology and explore the possibility of transversal links to paleoanthropological perspectives on the symbolic propensities of the human mind. This will reveal the cave paintings from the Upper-Paleolithic as a reliable window through which we can get a glimpse of the symbolic minds of our prehistoric, Cro-Magnon ancestors. Moreover, a neuroscientific perspective on the embodied human mind and human consciousness will not only yield the possibility of a neurological bridge to the Upper-Paleolithic, but also raises the possibility that our universal human capacity for altered states of consciousness may not only provide a link to the spectacular scope of prehistoric human imagination, but may also reveal a form of shamanism as a plausible interpretation of the earliest forms of religious imagination. Third, religious imagination will emerge as central to any paleoanthropological or theological definition of human uniqueness. This proposal will challenge the ability of neuroscience and cognitive psychology to effectively explain religious experience: although biological origins have directly shaped human origins and human understanding, the genesis of religions, so unique to humans, is not something that we can unproblematically extrapolate from earlier explanations in biology or neuroscience.

Human Uniqueness and Language

In Chapter Four we saw that Steven Mithen has argued that seeds for the cognitive fluidity of the human mind were sown with the increase of brain size that already began around 500,000 years ago. This was directly related to the later evolution of a grammatically complex social language. On Mithen’s more gradualist view, as social language switched to a general-purpose language, individuals acquired an increasing awareness about their own knowledge of the non-social world. Consciousness then adopted the role of a comprehensive, integrating mechanism for knowledge that had previously been ‘trapped’ in separate specialized intelligences (cf. Mithen 1996:194). The first step towards cognitive fluidity appears to have been an integration between social and natural history intelligence in Early Modern Humans around 100,000 years ago. The final step to full cognitive fluidity, the ability to entertain ideas that bring together elements from normally incongruous domains, most probably occurred at different times in different populations between 60,000 and 30,000 years ago. This involved an integration of technical intelligence, and led to the cultural explosion we are now calling the appearance of the human mind (cf. Mithen 1996:194). In Chapter Four we also saw clear differences of opinion as scholars in paleoanthropology and archeology approached this rather spectacular emergence of the human mind differently. From a theological perspective, however, irrespective of differences in scientific interpretation and perspectives, it was this important step in the evolution of the human mind that ultimately enabled our species to design complex tools, to create art, and to discover religious belief.

This, of course, leads to the broader question, what can we reconstruct today about the evolution of culture, and any unique cultural capacities, in humans? In his most recent work Rick Potts has discussed this question in depth and pointed out, first of all, that scholars in primatology and paleoanthropology today generally assume that a common ancestry of culture exists among at least the great apes and humans, including the oldest human ancestors (Potts 2004:249; also 1996). What this means, is that the concept of culture, normally exclusively applied to human beings, is now also applied to chimpanzees by primatologists who have demonstrated geographic variation in the behavioral repertoires of these apes. These variations are described as ‘cultural’ because these apes are able to invent new customs and then pass them on independently within different social groups, where neither ecological nor genetic factors can account for the behavioral differences manifested between groups. The most well-known example here is differences in termite feeding: at Gombe, Tanzania, chimpanzees practice termite fishing with slender twigs that are prepared and the inserted into termite nests; by contrast, chimpanzees in Equatorial Guinea practice termite digging, and stout digging sticks are used to break open termite nests (Potts 2004:249).

A very different concept of culture is employed when Paleolithic archeologists and paleoanthropologists speak of culture, which almost always refer to stone tools. Here different artifacts and manufacturing techniques are equated with different, distinct cultures and are considered to indicate cultural change. It is in this sense that archeologists then speak of Oldowan culture, Acheulean culture, and Mousterian culture. In applying these terms, scientists assume that change in toolmaking methods and the proportion of distinct artifact types over time and space reflects the development of new bodies of cultural information, which evolving hominids became capable of inventing and sustaining.

In spite of these differences in using the concept ‘culture’, Rick Potts has argued persuasively that the quest for a common ground between primate culture, hominid culture, and human culture is scientifically sound and defines a way of studying the continuities between human and non-human primate behavior. On this view paleoanthropologists and primatologists share at least four elements of agreement on what constitutes cultural behavior (Potts 2004:251ff):

1. Culture is a system of non-genetic information transfer, which occurs across generations and among individuals of the same generation.

2. Cultural behavior is manifested in discrete forms, i.e., specific activities, implements, or systems of belief.

3. Geographic differentiation in behavior, i.e., differences between separated populations, is an important and distinctive common ground for cultural behavior, and has been well documented in chimpanzees, orangutans, and humans.

4. The potential for change across generations is a final hallmark of primate cultural behavior. In modern humans, cultural variations are cumulative: the inventions of many generations are stockpiled, creating vast repositories of social information. In nonhuman primates there is less evidence for such accumulation.

The really interesting question, of course, is how this shared concept of culture fares when compared to the behavioral deposits, or artifacts, left behind by early humans? Here too Rick Potts’ answer is persuasive and to the point. Potts has argued that the oldest material record of hominid behavior is about 2.5 millions years old and consists of assemblages of precisely and repetitively chipped and battered rocks that define Oldowan toolmaking. It used to be thought that Oldowan cores (the sharp-edged rocks that bear multiple flake scares) represented purposeful tool designs that were in the minds of Homo habilis toolmakers. Detailed studies have now shown, however, that these idealized forms were mainly ‘stopping points’ in a continuous process of knocking sharp flakes from rocks of different original shapes. In fact, over a span of 800 thousand years (from ca. 2.5 to 1.7 million years ago) the Oldowan largely consists of continuously varying artifact forms that resulted from the repetitive process of flaking stone, making sharp edges, and using rounded stones or the cores themselves to hammer and crush other objects (Potts 2004:252f.). The earliest Acheulean, around 1.7 million years ago, reflected an apparent breakthrough in the process of stone flaking. Hominid toolmakers were able, for the first time on a regular basis, to detach very large flakes, and when this was done and the piece then flaked around the perimeter, the first handaxes, or large cutting tools were make. What is important, as well as fascinating, is that the enormous distance between Africa and East Asia did not prohibit or hinder the making of tools very similar to one another, and they certainly point to similar cognitive and technological capabilities on Africa and East Asia. For Rick Potts this clearly implies that even on this large geographic scale, and across long stretches of time, cultural differentiation of hominid populations is not as apparent as once believed (Potts 2004:259f.).

When we now proceed to compare the rich body of archeological evidence to the common ground of modern ape and human culture, intriguing differences become apparent. Potts has argued that over the first two million years of the archeological record, early humans manifested a behavior system that differed from great ape and human culture. Potts has called this a paleocultural system, which was indeed characterized by the transmission of non-genetic information, yet the artifacts and inferred behaviors of early humans, until roughly 500,000 years ago, exhibited continuous variation, which points to ecological factors for an explanation of some of this variation (Potts 2004:260). At the same time, paleolithic toolmaking was also marked by long periods of stasis, hundreds of thousands of years over which stone flaking did not change in any systematic manner. In other words, separation in space and time did not necessarily imply distinct behavioral packages, or ‘cultures’, as the term is used by anthropologists and primatologists. What this means, is that while non-genetic transmission of culture exists in all great apes, other commonalities of ape and human culture are not homologous. Although bonobos and gorillas, for instance, exhibit complex social learning, tool-assisted behavior in the wild and consistent geographic variations in social behavior have yet to be demonstrated in these species. It would still be possible to argue, however, that a greater capacity for innovation and geographic differentiation of discrete behavioral variants emerged independently in chimpanzees and orangutans during the Pleistocene, parallel to the pattern in the human record (Potts 2004:261).

This finally leads us to the crucial question: when was it that modern human cultural behavior emerged, and under what conditions did this process of emergence take place? Potts has argued that vast environmental fluctuations have characterized the past several millions years and provided the critical context in which humans evolved. This is especially true of the past 700,000 years (cf. Potts 1996), which have comprised one of the most turbulent periods of environmental instability in earth’s history. As a consequence, the Pleistocene was a period of high species extinction, and lineages that did not become extinct seemed to have one of two options: either mobility and wide dispersal, which allowed these creatures to keep up with geographic shifts in their preferred climatic zone or food resources, or a greater degree of versatility or adaptability to a wider range of environmental conditions (Potts 2004:261).

It is precisely this capacity for versatility that Potts have identified as the ‘astonishing hallmark of modern humanity’ (Potts 1996; 2004). Never before has a single species of such ecological adaptability evolved, at least among vertebrates. Homo sapiens thus emerged as a result of its ancestral lineage having persisted and changed in the face of dramatic environmental variability. It is in this dynamic prehistoric environment that a suite of anatomical and behavioral shifts occurred: not only did the fastest rate of increase in brain size relative to body size take place over the past 700,000 years, but around 500,000 years ago the stone tools make by early hominids became more diversified with increasingly standardized forms (Potts 2004:262). At the same time social interactions also intensified. Although it has been suggested that home bases existed earlier in time, it was only around 400,000 to 300,000 years ago that the primary signals of modern human home-base behavior, namely hearths and shelters, became apparent in the prehistoric record.

As far as symbolic behavior is concerned, it already became clear earlier that a few artifacts between 250,000 and 70,000 years ago indicated that symbolic behavior began to be reflected in the things hominids made. The presence of pigment at least 230,000 years ago in central Africa suggest decorative capabilities in some early human populations (cf. McBrearty and Brooks 2000:524). However, as we saw in Chapter Four, a tremendous expansion of symbolic behavior occurred 50,000 to 30,000 years ago, manifested in body ornamentation, cave paintings, sculpture, and the first musical instruments (bone flutes). Innovation indeed started to soar, exemplified by the routine use of new materials such as antler and bone, in addition to stone, to create new kinds of implements and aesthetic objects (Potts 2004:263).

Most important for understanding the symbolic minds of these ancestors of ours, however, is language – one of the most elaborate forms of symbolic coding imaginable. Language, and the ability to refer to distant sources of water, food, and other ‘non-visible’ aspects of the natural and social environment (Potts 2004:263f.), may have made the difference between survival and extinction in a challenging environment. Symbolic language enables humans to create complex mental maps, to imagine ‘what if…’, to think in terms of contingencies, and to plan and create strategies for events that have not yet happened. And exactly relevant to this point, Hauser, Chomsky, and Fitch, in a recent article analyzing the evolution of the language faculty, have argued that the unique ability of recursion lies at the heart of uniquely human language, i.e., the ability to turn a finite set of elements (phonemes, words, syntactical rules, mental activities) into a potentially infinite array of discrete expressions and representations (cf. Hauser, Chomsky, Fitch 2002:1569ff.). Most scholars would also agree that animal systems of communication lack precisely the rich expressive and open-ended power of human language. Against this background Rick Potts has argued that, although it is difficult to see how it might have evolved via habitat-specific, directional selection, this infinitely inventive aspect of language does make sense as an evolved response to the type of complex, inconsistent settings in which Homo sapiens emerged (Potts 2004:261; 1993).

It is clear then, that a highly specific view of human uniqueness thus emerges in the work of Rick Potts. The origin of language, and of cultural capacities so distinctive to living humans greatly enhanced the chances of adapting to environmental instability, and this enhancement decoupled the early modern humans from any single ancestral milieu (Potts 2004:265). Trying to understand humanness from a paleoanthropological and archeological point of view inevitably reveals the overarching influence of symbolic ability, and thus for the means by which humans create meaning. Clearly then, human cultural behavior involves not only the transmission of non-genetic behavior, but also the coding of thoughts, sensations, things, times, and places that are not empirically available or visible. In this way Potts’ work becomes invaluable for an interdisciplinary dialogue with theology, because what we have here is an argument from science that not only the material culture of prehistoric imagery as depicted in the spectacular cave ‘art’ of France and Spain, but the heights of all human imagination, the depths of depravity, moral awareness, and a sense of God, must depend on this human capacity for the symbolic coding of the ‘non-visible’. This ‘coding of the non-visible’ through abstract, symbolic thought, enabled also our early human ancestors to argue and hold beliefs in abstract terms. In fact, the concept of God itself follows from the ability to abstract and conceive of ‘person’ (Potts 2004:265f.).

I believe that Potts has made a convincing argument that this ‘paleocultural system’ of early human behavior would not have made sense as a response to a world of certainty and stability. But it does make sense as a psychological and social response to a world of contingency: the need to create meaning, whether religious, ethical, philosophical, aesthetic, is in fact part of the ‘toolkit’ that Homo sapiens have evolved in its long journey of physical and spiritual survival. However much humans, therefore, share with primate or hominid culture, we cannot avoid acknowledging the emergence of distinctive cultural properties that highlight both the evolutionary continuities and discontinuities in the cultural behavior of Homo sapiens, earlier humans, and other primates. And the most distinctive discontinuity is found in the emergence of language and the symbolic capacity of the human mind. It is language that engages the interactive minds of the social group, and that enables the social world beyond an individual’s own lifetime to be defined symbolically. It is this astonishing dimension of human cultural behavior that is unique to modern humans and that suggests the origins of a spiritual sense. A sense of the ineffable, the sacred, the spiritual, is part and parcel of how humans beings have coped with their personal and social universe (Potts 2004:270), and in this coping process the role of language in the evolution of the uniquely human mind was crucial. Steven Mithen has argued that, as soon as language started acting as a vehicle for delivering information into the mind, carrying with it snippets of non-social information, a rather dramatic transformation of the nature of the mind began (cf. Mithen 1996:208ff.). At that point language switched from a social to a general-purpose function, and consciousness from a means to predict other individuals’ behavior to managing a mental database of information relating to all domains of behavior. Thus, as we saw earlier, a cognitive fluidity arose within the mind, and consequently, a mental transformation occurred, which physiologically implied no increase in brain size. This move, in essence, was the origins of the kind of symbolic capacity that is unique to the human mind.

Consequently, as we saw in Chapter Four, scholars like Steven Mithen, Ian Tattersall and Paul Mellars have all argued that knowing the prehistory of the human mind will provide us with a more profound understanding of what it means to be uniquely human. It certainly helps us to understand a little better the origins of art and of religion, and how these cultural domains are inescapably linked to the ability of the cognitively fluid human mind to develop creatively powerful metaphors by crossing the boundaries of different domains of knowledge. By definition this kind of symbolic language use can arise only within a cognitively fluid mind.

However, Steven Mithen’s archeological perspective on the evolution of language still leaves us with some important questions regarding the symbolic capacities of our human minds. Some of the crucial questions that scholars still wrestle with today are: first, when did modern human language arise, and second, what exactly was its function in an evolutionary context? Here, too, answers are given along the two well-known lines of current evolutionary and paleoanthropological debates: did language arise rather suddenly, in a punctuated leap at the very threshold of modern human existence, perhaps at the Middle to Upper Paleolithic boundary (cf. Lewin 1993:162)? Or did linguistic abilities develop gradually, reaching modern levels not through a sudden advance but through steady, cumulative increments? It is obviously very difficult to address the timing of language origins since language does not fossilize or impress itself directly on the archeological record. Paleontologists, therefore, have to look for indirect products of language capability, or for evidence from the anatomical structures that produce language, namely the brain and the vocal tract (Lewin 1993:163).

What seems to be clear is that the potential for language was fully realized when Upper Paleolithic people for the first time were neurologically equipped for language. An increasing number of scholars have also pointed to various areas of archeological evidence that point, directly or indirectly, to a dramatic enhancement of language abilities that seems to have coincided with the Upper Paleolithic: first, deliberate burial of the dead, which almost certainly, at least in a basic sense, had already begun in Neanderthal times; second, artistic expression, especially bodily adornment and image making (notably the painting of caves), which began only with the Upper Paleolithic; third, a clear and sudden acceleration in the pace of technological innovation and cultural change; fourth, the development of real regional differences in culture, an expression and product of social boundaries; fifth, evidence of long-distance contact and trade; sixth, a significant increase in size of living sites, for which complex language is a prerequisite for planning and coordination; seventh, the movement from the predominant use of stone technology to include other raw materials, such as bone, antler and clay (cf. Lewin 1993:163).

This combination of ‘firsts’ in human activity looks impressive, and seems increasingly to define the uniqueness of Homo sapiens from a paleoanthropological perspective. Although some scholars, of course, question the punctuational appearance of some of these elements, most find the evidence of these historically meaningful shifts persuasive support of the appearance of a complex, fully modern spoken language (cf. Klein 1999:590f.). In the light of the latest evidence, then, it is tempting to infer that the Upper Paleolithic was ushered in by a major enhancement of language abilities. What is most interesting for our purposes, however, is that the same kind of pattern is to be seen in that major area of archeological evidence, namely prehistoric art or imagery. As was argued in Lecture Four, activities such as engraving, sculpting, and especially painting, appear late in the prehistoric record, and coincided with the sudden emergence of innovation and rapid change that defines Upper Paleolithic tool technologies. If the ability to produce representational and symbolic images and decorative objects does relate to language abilities, the evidence of the archeological record would indeed point to dramatic enhancement late in human prehistory (cf. Lewin 1993:166).

It is exactly for this very close link between creative prehistoric imagery and language that scholars like Iain Davidson and William Noble have argued. In his argument for a very direct link between language and symbolic abilities, Davidson takes a comparative approach that juxtaposes data from Europe with that from Australia, and then argues that the similarities in the development of early image making clearly shows the universal use of art to reflect the negotiation of environmental (i.e., both natural and social) relationships. Davidson also argues, rather impressively, that the most significant European influence on the cultural development of modern humans is not to be found in the sculpture of the Classical Greeks, the paintings of the Italian Renaissance, the plays of Shakespeare, or the musical tradition of Mozart and Beethoven, but precisely in the paintings and engravings of the Upper Paleolithic, between 30,000 years ago and 10,000 years ago, in a small region of south western Europe (cf. Davidson 1997:125).

Davidson also argues that early humans worked out their relationship with their environment and with each other through this ‘art’, and sees the burst of image making after 40,000 BP as reflecting the way that these ancestors of ours explored the limits and possibilities of the power of their recently discovered symbolically based communication. Because of this, most scholars in the field would take the Upper Paleolithic as the standard for recognizing symbolism, even if in a sense it is anomalous, because symbolism did not emerge elsewhere in the world populated by Homo sapiens at that time (cf. Davidson 1997:125). For Davidson this symboling power is tied directly to the origins of language: it would have been impossible for creatures without language to hold opinions about the making or marking of surfaces that make them art. For this reason Davidson argues that it is precisely these supremely important artistic artifacts from the Upper Paleolithic that give us unique insights into evolutionary processes, into the evolution of human behavior, and into the very nature of what it might have meant to be a modern human.

Davidson takes as his fundamental assumption throughout that language emerged fairly late in human evolution (cf. Davidson 1997:126; also Noble and Davidson 1996). He recognizes that the vocal apparatus evolved gradually over the course of human evolution, but argues that the actual transition between language absence (although certainly including vocal and other communication) and language use involved the recognition of symbols. What is crucial, is that language is distinguished from other forms of communication not only by the fact of modes of communication like speech, signs, or writing, but by the use of symbols in any or all of these modes of communication (cf. Davidson 1997:126). In this sense the emergence of language goes hand in hand with the recognition of symbols, This does indeed mean that we could not have art without language, but it does not mean that the origins of language can be identified with the origins of art. Davidson has in fact argued that the earliest evidence which requires an interpretation that there were people who already must have had language, is the fact of the colonization of Australia around 60,000 years ago. This seems to be 20,000 years earlier that the Upper Paleolithic of Europe (cf. Davidson 1997:126f.). The important question now is, what does the rather late origin of language mean for our understanding of prehistoric art? For Davidson one of the most distinctive features of language is the arbitrariness of symbols, and how that necessarily results in inherent ambiguity, especially when compared to pre-linguistic communication systems (cf. the complex calls of vervet monkeys) which have no possibility of ambiguity because it has been honed by natural selection. One way to cope with the proliferation of this kind of ambiguous creativity, was to produce emblems or signs which we, even today, can recognize as in some sense iconic. Successful communication, therefore, requires means of identification that the utterances are trustworthy. We should, therefore, not be surprised to find these kinds of emblems among early language users (cf. Davidson 1997:126f.). We should also not be surprised, I think, that we too are still fascinated by the enigmatic character of these symbolic images and signs.

This argument, that paleolithic art is symbolic, not just decorative art, is considerably strengthened by what has already been discussed in Chapter Four, namely Margaret Conkey’s persuasive arguments against trying to capture the generic ‘meaning’ of paleolithic art as a single, inclusive, empirical category or metatheory of our inquiry, and for a more contextual understanding of the ‘meaning’ of this art as enmeshed in the social context of its time. On this view, the original meaning can only be said to exist through the contexts in which it was first produced as individual paintings or parts of paintings (cf. Davidson 1997:128). What this really means is that ‘meaning’ is not a property of paleolithic art in itself, but of the interaction, then and now, between the human agents and the material. We also, in our own relational, interactive interpretations of this art, discover and produce meaning. Therefore, the ‘meaning’ we find in the earliest art produced by people like us clearly is a product of our own interpretative interaction with this art. What again emerges here is an important convergence between theological and paleoanthropological methodology, a truly postfoundationalist argument for meaning that, as I argued in Chapter One, implies that we relate to our world(s) through interpreted experience only.

When viewed like this, the Upper Paleolithic tradition of prehistoric ‘art’ emerges as an evolving tradition (or traditions) that has had, and still has, the capacity to reveal distinct regularities, and not just western European particularities, about the evolution of human behavior (cf. Davidson 1997:133)1. Davidson has also argued that personal ornamentation is earlier in the surviving evidence than the ‘making of places’ (cave paintings). In the evolutionary process of ‘art’ in the Upper Paleolithic era this does not imply that there was an inevitability of ‘progress’ from personal decoration to the painting of the caves. But personal decoration was indeed an early part of the complex of symbolic representation in the Upper Paleolithic of Europe. What Davidson is suggesting, is that, although the earliest language, and hence symbolism, may have left no material trace, on both continents the newly arrived humans had only recently discovered language and its symbolic properties. And in this context they also discovered personal decoration and cave painting (cf. Davidson 1997:138; 147f.).

But what more can be said about language and symbolism in prehistoric cave paintings, that most famous manifestation of Upper Paleolithic ‘art?’ One of the most fascinating examples of the way in which prehistoric cave art reveals some distinct regularities is found in the so-called hand stencils, or hand prints. The earliest images in Upper Paleolithic Cave Art are indeed the famous hand prints, especially those from Gargas in the French Pyrenees, and are now confirmed by the early dates from those in Cosquer, the famous ‘cave beneath the sea’2. The production of hand prints on cave walls is one of the truly universal features of expressive human behavior, produced all over the world and at almost all times since there have been humans (cf. Davidson 1997:148f.). Although Iain Davidson has maintained that we have no way of ever knowing exactly what they meant, Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams, as we saw in Chapter Four, have now persuasively argued for an interpretation that sees these famous hand prints as shamanistic ‘touchings of the other world’, and thus for an unmistakable ritualistic, religious interpretation of these mysterious, ubiquitous signs.

From a paleoanthropological point of view symbolism should, therefore, be seen as part and parcel of turning communication into language, but the use of symbols separate from language, as in the case of cave paintings and abstract signs, could only have been a product of language (cf. Davidson 1997:153). What this implies is that whatever symbolic, expressive quality those spectacular prehistoric cave painting had in south western France and in the Basque Country of Northern Spain, they could only have had because of the linguistic context in which they must have been created. Hence the imagination, productivity and creativity we associate with humans is very much a product of language, which makes language and symbolic abilities central to a definition of embodied human uniqueness.

In their Human Evolution, Language and Mind (1996), Iain Davidson and William Noble have made an even more detailed case for this close relation between language and prehistoric art. At the heart of this argument is the conviction that the making of images to resemble things can only have emerged historically in communities with shared systems of meanings, and shared systems of meaning are mediated through language. Davidson and Noble’s main argument, however, is that the development of language and the development of image-making are interdependent, each facilitating the other. In this sense representational images in prehistory should actually be seen as the imprint of language in a tangible, material form (cf. also Lewin 1993:166). For Noble and Davidson human ‘mindedness’ and ‘minded’ behavior only arise within the socially constructed context of linguistic communication, which is why the appearance of symbolic behavior like cave paintings is so directly related to language, and why both language and symbolic behavior are very late developments, appearing no more than fifty thousand years ago (cf. Mithen 1997:269ff.).

What I see emerging here is an interpretation of the embodied human mind functioning as a ‘mindedness of behavior in context’, especially in its very specific historical, social, and paleocultural context. Crucial to Noble and Davidson’s argument is how communication between humans came to be unquestionably intentional, and they answer by seeing language as social interaction where those practices which happen to be unique to humans interactively recruit the structures of the brain, rather than just being determined by them. Such practices obviously depend on prior structural evolution, but it is these cultural practices that interact with brain structures (cf. Noble and Davidson 1996:18). It is in this sense that minded human behavior is linguistic and essentially interactive, and that human minds are socially constructed. Against this background it can be argued that in early humans, the physical acts of throwing and pointing actually led to iconic gestures, which in their turn made possible the transformation of communication into language. The fact that a gesture could be a meaningful object for perception, facilitated the remarkable symbolic discovery that one thing can stand for another. This discovery, for Noble and Davidson at least, was an all-or-nothing event which can not be explained in gradualist terms (cf. also Corbey and Roebroeks 1997:917ff.). This radical position leads them to reject a gradualist approach to the evolution of language, and along with that the possibility of ‘protolanguage’: if a form of communication was not language as we actually know it, it would be misleading to refer to it as language at all (cf. Noble and Davidson 1996:8ff.)3.

On this view the discovery or emergence of language was more a matter of behavior than of evolutionary changes in biology alone. Language as a symbolic communication system created mindedness, being aware of experience and knowledge, being able to judge and plan and thus better control the future. This ability finally released early humans partially from the immediate contingencies of a specific natural environment, enabling them to plan logistically in all kinds of environmental settings, to abstract, to differentiate between ‘us’ and ‘them’, to construct notions about the supernatural, and to reflect on past, present, and future (cf. Corbey and Roebroeks 1997:917ff). Noble and Davidson thus effectively argue that Upper Paleolithic tools, art, shelters, burials, and especially also the colonization of islands, are the first valid indicators of the kind of planning that depended on language. This view is consistent with majority views today about the late origin of the modern human adaptation (cf. Parker 1997:579).

By now is should be clear that throughout the history of paleoanthropological research, one of the primary questions has always been, when did humans begin to think, feel, and act like humans? Central to this question has always been the issue of cognition or awareness, and how it might be recognized in its initial stages (cf. Simek 1998:444f.). Steven Mithen’s answer to this question, as saw earlier, was an evolutionary approach to the origins of the human mind, and the development of a three stage typology of cognition that follows the evolution of domains of intelligence from the earliest members of the genus Homo through to their final integration in modern humans. Only in the final phase, in Homo sapiens, do we find a dramatic behavioral break, a ‘big bang’ of cognitive, technical and social innovation with the rise of cognitive fluidity, the final phase of mind development. William Noble and Iain Davidson, on the other hand, see one development, namely language, as pivotal in the evolution of human cognition. Here social context is seen as a primary selective force, and language, symbolization and mind are integrated into an explanatory framework for the evolution of human cognition, centered on the human ability to give meaning to perceptions in a variety of ways. Ultimately Noble and Davidson see language as emerging out of socially defined contexts of communication, encouraged as a more efficient form of gesture, with the selection of language occurring precisely because of its efficiency and flexibility (cf. Simek 1998:444f.).

My discussion in this chapter of the important work of Rick Potts, Steve Mithen, and of William Noble and Iain Davidson, against the background of our earlier analyses of human origins and human uniqueness, has shown how extremely complex and interdisciplinary the field of paleoanthropology has become. For a philosophical theologian like myself, who normally lives and works outside of this field, it has at least become clear that the origin of human consciousness and cognition, like most aspects of human behavior, were part of the complex mosaic of evolution and in fact a convergence of many evolutionary trajectories. Jan F. Simek puts it persuasively: over time elements of the brain itself may have evolved in different ways, and at different rates. Various human behaviors, including the capacity for symboling and communication, also developed in distinctive ways along particular pathways. These pathways were subject to diverse selective forces over time and space, and may ultimately have converged in different areas in different forms. Thus, the Late Pleistocene relationship between biology and behavior in the Near East may well have differed from that in Europe, and art could ‘explode’ in one area and not (yet) in another (cf. Simek 1998:444f.). What should be increasingly clear for the theologian in dialogue with these sciences, is that the diverse, and sometimes conflicting, voices in paleoanthropology are all adding importantly to an emerging mosaic of what it means to be distinctively human.

Human Uniqueness and the Symbolic Mind

The important discussion in paleoanthropology and archeology on language and the symboling mind is enhanced if we transversally connect this dialogue to voices from the neurosciences and neuropsychology, where the focus has quite specifically been on the symbolic propensities of the human mind. A specific focus on the human brain may add different perspectives to this discussion and also the argument that language can be seen as the major cause, not just the consequence, of human brain evolution. Some would see this as indicating a gradual increase in language competence throughout human prehistory (at least post-Homo), which prepared the human brain for the cognitive leap that occurred with the appearance of behaviorally modern humans.

In his The Symbolic Species (1997), Terence Deacon takes up the theme of human uniqueness and quite deliberately links it to the paleoanthropological discussion on the unparalleled cognitive ability of our Cro Magnon ancestors in the Upper Paleolithic. For Deacon it is clear that as humans we think differently from all other creatures on earth, and we can share those thoughts with one another in ways that no other species even approaches. In his own words:

Hundreds of millions of years of evolution have produced hundreds of thousands of species with brains, and tens of thousands with complex behavioral, perceptual, and learning abilities. Only one of these has ever wondered about its place in the world, because only one evolved the ability to do so (Deacon 1997:21).

As humans we very consciously inhabit a world full of abstractions, impossibilities, and paradoxes. We alone brood about what did not happen, and we alone ponder what it will be like not to exist. We tell stories about our real experiences and invent stories about imagined ones, and we even make use of these stories to organize our lives. In a very real sense, then, we live our lives in this shared virtual world (cf. Deacon 1997:22). For Deacon this remarkable ability has everything to do with language, and with the absence of language in other species. The doorway into this virtual world was opened to us alone by the evolution of language. The human brain is different, not just in size, but precisely in our unique and complex mode of communication, language. In a very specific sense only humans communicate with language, and this unique form of communication is special and far more precise and rapid than any other kind of communication. No other form of animal communication has the logical structure and open-ended possibilities that language has, and the underlying rules for constructing sentences are so complicated that it is hard to explain how they could ever be learned. Therefore, although other animals communicate with one another, this communication resembles language only in a very superficial way (for example, by using sounds) and there is no evidence that these modes of communication have the equivalent of anything like words, much less nouns, verbs, and sentences (cf. Deacon 1997:12f.). Deacon also investigates how language differs from other forms of communication, and why other species encounter virtually intractable difficulties when it comes to learning even simple language. The human brain, however, has evolved to overcome these difficulties. There is an unbroken continuity between human and nonhuman brains, and yet, at the same time there is a singular discontinuity between human and nonhuman minds, between brains that use this form of communication and brains that do not.

But language is not only a highly unusual from of communication, it is also the outward expression of a highly unusual mode of thought, namely symbolic representation (Deacon: 1997:22). We indeed seem to be the only species that has evolved the ability to communicate symbolically. The questions about human origins that so deeply fascinate us cannot, therefore, be answered only in a paleontological way by inquiring about who were our ancestors, how they came to walk upright, or how they discovered the use of stone tools. For Deacon the broader question should be a neuroscientific one, namely where do human minds come from? Thus, the missing link that we hope to fill in by investigating human origins is not so much a gap in our own family tree, but a gap that separates us from other species in general. Deacon rightly argues that this is a Rubicon crossed at a specific time and within a specific evolutionary context. If we could identify what was different on either side of this divide – differences in ecology, behavior, anatomy, and especially, neuroanatomy – perhaps we could find the critical change that catapulted us into this unprecedented world full of abstractions that we call human (cf. 1997:23).

It is, therefore, not just the origins of our biological species that we are trying to explain, rather, it is especially the origin of our novel form of mind that we are trying to understand. The most critical piece of missing information regarding the origin of humans is exactly the ancestral hominid brain, because the internal microarchitecture of these brains left no fossil trail (cf. 1997:24). Therefore, the point is not that we humans are better or smarter than other species, or that language is impossible for them. It is simply that these differences are not a matter of incommensurate kinds of language, but rather that these nonhuman forms of communication are something quite different from language. In fact, of no other natural form of communication is it legitimate to say that ‘language is a more complicated version of that’. In fact, this kind of analogy would ignore the sophistication and power of animals’ own distinctive nonlinguistic communication. At the same time increased cognitive abilities do not necessarily represent some form of ‘progress’ in evolution. According to Deacon, the idea of progress in evolution is an unnoticed habit left over from a misinformed sense of seeing the history of the living world in terms of design. Evolution certainly is an irreversible process, a process of increasing diversification – but only in this sense does evolution exhibit a consistent direction (1997:29ff.).

The most important issue in defining the difference between language and other modes of communication is actually not the complexity of language as such. The most salient difference between language and non-language communication is the common, everyday miracle of word meaning and reference. This is why it was not grammar, syntax, or vocabulary that have kept other species from evolving languages: it is just the simple problem of figuring out how combinations of words refer to things. This uniquely human from of communication/mode of reference can be called symbolic reference.

Somehow, despite our cognitive limitations, our ancestors found a way to create and reproduce a simple system of symbols, and once available, these symbolic tools quickly became indispensable. Because this novel form of information transmission was partially decoupled from genetic transmission, it sent our lineage of apes down a novel evolutionary path – a path that has continued to diverge from all other species ever since (Deacon 1997:45).

Therefore, if the human predisposition for language has been honed by evolution, then our unique mentality must also be understood in these terms. The implications for brain evolution are profound: the human brain should reflect language in its architecture the way birds reflect the aerodynamics of flight in the shape and movements of their wings. Moreover, what is most unusual about language, i.e., its symbolic basis, should then correspond to that which is most unusual about human brains, i.e., a radical re-engineering of the whole brain, and on a scale that is unprecedented. In the co-evolution of the symbolic brain and language, then, two of the most formidable mysteries of science converge. Basically, though, if symbol-learning is the threshold that separates us from other species, then there most be something unusual about human brains that helped to surmount it. We have to ask, therefore, what other changes in brain organization correlate with this global change in brain size, and what are their functional consequences? (cf. Deacon 1997:148).

On this point Deacon has moved close to Ian Tattersall’s point of view, discussed in Chapter Four, and the statement that we humans are not just more intelligent than other species, we are actually differently intelligent (cf. Tattersall 1998:58ff.). The difference between human and nonhuman brains may be far more complex and multifaceted than simply an increase in extra neurons over and above the average primate or mammal trend (cf. Deacon1997:224). Deacon also closely approaches Steven Mithen’s idea of cognitive fluidity. Individual linguistic symbols are not exactly located anywhere specific in the brain, but the brain structures necessary for their analysis seem to be distributed across many areas. Deacon suggests that the first use of symbolic reference by some distant ancestors changed how natural selection processes have affected hominid brain evolution ever since. In a very real sense this now means that the physical changes that make us human are the incarnations of the process of using words. This is explained further by a subtle modification of the Darwinian theory of natural selection, as outlined more than a century ago by James Mark Baldwin, and often called ‘Baldwinian evolution’, although there is nothing non-Darwinian about the process. Baldwin suggested that learning and behavioral flexibility can play a role in amplifying and biasing natural selection. What Baldwin’s theory explains, then, is how behaviors can affect evolution, which is not the same as the Lamarckian claim that responses to environmental demands acquired during a lifetime could be passed on directly to offspring (cf. Deacon 1997:322).

What this means is that the remarkable expansion of the brain that took place in human evolution was not just the cause of symbolic language but in a sense rather a consequence of it. Each assimilated change enabled even more complex symbol systems to be acquired and used, and in turn selected for greater prefrontalization (cf. 1997:340ff.). More than any other species, then, hominids’ behavioral adaptations have determined the course of their physical evolution, rather than vice versa. For instance, stone and symbolic tools, which were initially acquired with the aid of flexible ape-learning abilities, ultimately turned the tables on their users and forced them to adapt to a new niche opened by these technologies. The point of origin of ‘humanness’ can now be defined as that point in our evolution where these tools became the principal source of selection on our bodies and our brains, and in this sense is the ‘diagnostic trait’ of what Deacon has called Homo symbolicus (Deacon 1997:345). On this view it is clear that the importance of toolmaking as a learned skill, not a physical trait, was passed on not genetically but behaviorally. We cannot, of course, assume that all tool users were our ancestors, but the introduction of stone tools and the ecological adaptation they indicate also marks the presence of a socio-ecological predicament that demanded a symbolic solution. For Deacon stone tools and the use of symbols must both, then, be seen as the architects of the Australopithecus-Homo transition, and not just as its consequences. As a result, the large brains, stone tools, reduction in dentition, better opposability of thumb and fingers, and more complete bipedality found in post-australopithecine hominids van now be seen as the physical echoes of a threshold already crossed (cf. Deacon 1997:348).

What is interesting to observe in this highly plausible argument, is a very clear convergence between Terrence Deacon’s views and the views of evolutionary epistemologist Franz Wuketits on the evolution of human cognition, which we discussed in Chapter Two. For Deacon, as for Wuketits in his hypothetical realist approach to evolutionary epistemology, the evolutionary interactive dynamic between social/environmental and biological processes was the architect of modern human brains. For Deacon it is also the key to understanding the subsequent evolution of an array of unprecedented adaptations for language. Closely echoing Steven Mithen’s views in cognitive fluidity, Deacon can, therefore, conclude that once symbolic communication became essential for one critical social function, it also became available for recruitment to support dozens of other functions as well. And as more functions came to depend on symbolic communication, it would have become an indispensible adaptation (cf. Deacon 1997:352).

However, if the primary mystery of language is the origin of symbolic abilities, the second mystery is how most symbolic communication became dependent on one highly elaborated medium, namely speech (cf. 1997:352f.). For Deacon, what is certain is that the development of skilled vocal ability was almost certainly a protracted process in hominid evolution, not a sudden shift. The incremental increases in brain sizes over the last 2 million year progressively increased cortical control over the larynx, and this was almost certainly both a cause and a consequence of the increasing use of vocal symbolization. In this sense, then, early symbolic communication would not have been just a simpler form of language, it would have been different in many respects as a result of the different state of vocal abilities. On this view it becomes highly plausible to assume that our prehistoric ancestors used languages that we will never hear and communicated with symbols that have not survived the selective sieve of fossilization. And as far as prehistoric ‘art’ goes, Deacon seems to be in complete agreement with Iain Davidson: it is almost certainly a reliable expectation that a society which constructed complex tools and spectacular art also had a correspondingly sophisticated symbolic infrastructure. Moreover, a society that leaves behind evidence of permanent external symbolization in the form of paintings, carvings, and sculpture, most likely also included a social function for this activity. And that is why material archeological artifacts are one of the few windows through which we can glimpse the workings of the ‘mental’ activity of a distant prehistoric society (cf. Deacon 1997:366). And that is why, I would add, the cave paintings of the upper Upper Paleolithic might be the only reliable window through which we can get a glimpse of the minds of our prehistoric, Cro Magnon ancestors. This rather spectacular phase in modern human behavior should, therefore, be seen as a source of evidence for the first use of symbols, the origin of speech, and the origin of religion. And even if scientists differ, sometimes markedly, about the timing, the pace, the impact of the evolution of the human mind, of its symbolic propensities and its close ties to language, as theologians in an interdisciplinary dialogue on human origins we can move beyond the details of the controversies and glean important facts about human uniqueness and the origin of a religious capacity from these diverse sciences. The challenging task will be to identify those shared concerns, and those transversal moments that will enable us to translate from theology to science, and back to theology.

For a neuroscientist like Deacon, then, it is clear that as far as paleolithic art goes, the first cave paintings and carvings that emerged from the Upper Paleolithic period do give us the very first direct expression of the symbolizing human mind. In Deacon’s own words:

They are the first irrefutable expressions of a symbolic process that is capable of conveying a rich cultural heritage of images and probably stories from generation to generation. And they are the first concrete evidence of the storage of such symbolic information outside of a human brain (cf. 1997: 372).

What has now become clear in our discussion of Steven Mithen’s, Ian Tattersall’s, Rick Potts’, William Noble and Iain Davidson’s, and Deacon’s work, is that human mental life includes biologically unprecedented ways of experiencing and understanding the world, from aesthetic experiences to spiritual contemplation. The origins of many of these most distinctive human traits are deeply intertwined with the origins of language. Language is without doubt the most distinctive human adaptation. In fact, both the special adaptations for language and language itself have played important roles in the origins of human moral and spiritual capacities (cf. Deacon 2003:504ff.). Assessing the origins of these abilities, however, is complicated by the fact that no direct consequences of language use are preserved in the fossil record. In a recent article, Deacon makes the important point that the spectacular paleolithic art and the burial of the dead, though not final guarantees of shamanistic or religious-like activities, do suggest strongly the existence of sophisticated, symbolic reasoning. And, important for the gradual, piecemeal evolution of human symbolic capacities in Africa that scholars like Rick Potts and David Lewis-Williams have argued for, these earliest examples of expressive symbolism in southwestern Europe can be understood not so much as evidence for the initial evolution of symbolic abilities, but rather for their first expression in durable media. (cf. Deacon 2003).

Like most of the voices from evolutionary epistemology and paleoanthropology I discussed earlier, it is significant that a neuroscientist such as Terrence Deacon can also conclude that the symbolic nature of Homo sapiens explains why mystical or religious inclinations can indeed be regarded as an essentially universal attribute of human culture (cf. Deacon 1997:436). As we saw earlier, there is in fact no culture that lacks a rich mythical, mystical, and religious tradition. The co-evolution of language and brain not only implies, however, that human brains have been reorganized in response to language, but also alerts us to the fact that the consequences of this unprecedented evolutionary transition for human religious and spiritual development must be understood on many levels as well. Deacon argued recently that there are reasons to believe that the way that language can symbolically refer to things provides the crucial catalyst that initiated the transition from species with no inkling of the meaning of life into a species where questions of ultimate meaning have become core organizers of culture and consciousness. It is these symbolic capacities that are ubiquitous for humans, and largely taken for granted when it comes to spiritual and ethical realms. For Deacon this is precisely where crucial differences in ability mark the boundary that distinguishes humans from other species. It is in this sense that one could say that the capacity for spiritual experience itself can be understood and an emergent consequence of the symbolic transfiguration of cognition and emotions (cf. Deacon 2003).

Against this background it again becomes clear why it can be argued that there is in fact no culture that lacks a rich mythical, mystical, and religious tradition, and that mythology and imagination is the mark of the modern human mind, the creation of worlds shared in the medium of language (Lewin 1993:177). The predisposition to religious belief indeed is one of the most complex and powerful forces in the human mind, one of the universals of human behavior. The question, of course, is how this kind of force might spring from the font of consciousness? When humans became aware of themselves as individuals with feelings and motivations, they not only imaginatively attributed similar feelings to other humans, but also to other animals and to inanimate objects of the world. From the moment of consciousness, then, there has been a universal urge to account for the rest of the world, to tell stories of how things came to be, which forces were good, which evil, and how they might be influenced. And with awareness of self comes awareness of death. Therefore, as in the case of the symbolic and enigmatic nature of the cave paintings from the Upper Paleolithic, also the practice of burial and the death awareness that must have gone along with it, provide the paleoanthropologist and archeologist with the possibility of gleaning from the past something of the level of conscious imagination in our distant ancestors’ minds (cf. Lewin 1993:177). And it is this conscious imagination that seems to have naturally, and unambiguously, included symbolic, religious imagination.

* * * * * *

Terrence Deacon’s argument that the spectacular cave ‘art’ from the Upper Paleolithic, as well as the burial of the dead that accompanied it strongly suggest shamanistic or religious-like activities (cf. Deacon 2003), resonates remarkably well with Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams’ intriguing proposal for a shamanistic interpretation (cf. Chapter Four) of at least some of the imagery from this important prehistoric period. In his most recent work The Mind in the Cave (2002), David Lewis-Williams has returned to this theme and developed a much stronger argument for seeing neuroscience, as well as neuropsychological research on altered states of consciousness as providing the principal access to what we might know today about the mental and religious life of the humans who lived and painted in western Europe during the Upper Paleolithic. I now will return to this interpretation of Upper Paleolithic imagery and not only argue for the plausibility of this proposal, but also illustrate how it enhances the interpretation of a select number of some of the most famous cave paintings from the Upper paleolithic in Europe. In the process a remarkable consonance with the postfoundationalist methodology I have proposed for interdisciplinary dialogue in Chapters One and Four, will emerge and further solidify my attempt to find transversal connections between paleoanthropology and theology.

As has become abundantly clear by now, in spite of the remarkable progress in paleoanthropology and archeology it often seems that we are still not closer to knowing why the people of the Upper Paleolithic penetrated the deep limestone caves of France and Spain to make spectacular images in total darkness. We still do not really know what the images meant to those who made and to those who viewed them, and the great mystery of how we became human, and in the process began to make art, continues to tantalize us. In spite if this, however, David Lewis-Williams believes that a century of research has indeed given us sufficient data, the ‘material conditions’ to attempt a persuasive, general explanation for a great number of Upper Paleolithic art. Moreover, we are now in a position to explain some hitherto inexplicable features of the imagery and its often bizarre contents. It is in this sense, then, that Lewis-Williams has argued that what is needed is not more data, but rather a radical rethinking of what we already know (cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:7f.).

In developing his own methodology for approaching this interdisciplinary problem, David Lewis-Williams, echoing Margaret Conkey’s rejection of metatheories for the interpretation of prehistoric imagery (cf. Chapter Four), shies away from overly generic explanations, while at the same time avoiding the over-contextualization of some relativist forms of interpretation. Lewis-Williams’ sensitivity for contextuality will emerge as a focus on the social and historical context of our ancestors from the Upper-Paleolithic. A keen sense for embodied materiality also drives him to seriously consider the role of intelligence and consciousness in prehistory. He argues that most researchers have consistently ignored the full complexity of human consciousness and have then presented us with a one-sided view of what it is to be an anatomically and cognitively fluid modern human being (cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:9). It is against this kind of rich background that he proceeds to examine the interaction of mental activity and social context.

Lewis-Williams has argued that for scientific work to present us with ‘better’ explanations it has to be focused on verifiable, empirical facts, and any hypothesis must relate explicitly to the observable features of specific data. It also has to be internally consistent in that no part of a hypothesis should contradict any another. Most importantly, though, any hypothesis that covers diverse fields of evidence is always more persuasive than one that pertains to only one, narrow type of evidence. In this sense complementary types of evidence that converge to address the complex problems posed by Upper Paleolithic ‘art’ can in fact produce persuasive hypotheses. This points directly, I believe, to the superiority of an interdisciplinary approach to issues in paleoanthropology and, by implication, in theology. It is in this sense too that useful hypotheses have strong heuristic potential, and as such lead to further creative questions and research (cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:49). Lewis-Williams also argues that for us to understand the historical trajectory of Upper-Paleolithic research, we have to be especially alert to the social embeddedness of scientific work and research (cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:49). I believe this lends strong support to the fact that in our own interactive relationship with paleolithic imagery, even if the ‘original meaning’ of these images are lost forever, a sense of patternedness will emerge that reveals enigmatic narrative structures, even of the original narratives are lost forever,

For David Lewis-Williams, allowing for the effects of social contexts, while at the same time emphasizing a real historical past and the possibility of constructing hypotheses that may approximate this past, now surfaces as a key epistemological principle, and we can now proceed to address the enigma of what happened to the human mind in the caves of Upper Paleolithic western Europe. To try to unlock the enigma of these images, we must therefore look more closely at the human brain, the mind, intelligence, and what Lewis-Williams has called the shifting, mercurial consciousness of human beings (cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:68). As a first step, Lewis-Williams wants to distinguish between human intelligence and consciousness and how this distinction may help to clarify what was happening to the Upper-Paleolithic mind in the caves of western Europe. We saw earlier that the amazing behavioral changes that culminated in the Upper Paleolithic, was slowly and sporadically assembled in Africa. This history clearly points to the fact that a kind of human consciousness can be presupposed that was alien to Neanderthals and that quite specifically allowed for symbolic conceptions of an ‘alternate reality’(cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:101). This leads directly to questions as to the evolution of intelligence and the very specific role of human consciousness in this process. For Lewis-Williams this directly implies what I have called a transversal approach to interdisciplinary research, precisely by incorporating ‘strands of evidence’ from neuroscience and neuropsychology into paleoanthropology. This kind of transversality is exemplified by his ‘cabling’ method of weaving together perspectives and arguments from different disciplines so as to sustain a specific hypothesis about the relationship between brain, mind, and the earliest forms of art (cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:103).

Lewis-Williams is rightly critical of any over-emphasis on intelligence, and the evolution of intelligence, that has marginalized the importance of the full range of human consciousness in human behavior. This reveals a one-sided focus on a ‘conciousness of rationality and intelligence’, and has marginalized the fuller spectrum of human consciousness by suppressing certain altered states of consciousness as irrational, marginal, abberant, or even pathological. This is especially true of altered states of consciousness, which in science and even within mainstream religion normally has been eliminated from investigations of the deep past. In a move closely reminiscent of Antonio Damasio’s work, Lewis-Williams suggests that we think of consciousness not as a state, but as a continuum, or spectrum of mental states (cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:121ff.). Following the work of Colin Martindale (1981) Lewis-Williams first describes the spectrum of states of consciousness that encompasses a trajectory from being fully awake to a state of sleeping. On this trajectory as we drift into sleep we pass through the following six phases:

– waking, problem-oriented thought.

– realistic fantasy

– autistic fantasy

– reverie

– hypnagogic (falling asleep) states, and

– dreaming.

In waking consciousness we are concerned with problem-solving, usually in response to environmental stimuli. We then become disengaged from those stimuli, and different states of consciousness begin to take over. First, in realistic fantasy we are oriented to problem-solving. These realistic fantasies grade into more autistic ones, i.e., one that are less connected to external reality. In this state our thoughts are far less directed, and image follows image in no narrative sequence. These then shade over into hypnagogic states that occur as we fall asleep. Sometimes these hypnagogic imagery is startlingly vivid and leads to what is called hypnagogic hallucinations, where someone would start awake and believe that their imagery is real. These hypnagogic imagery may be both visual and aural. And finally, in dreaming a succession of images appears, at least in recall, as a narrative. Focusing on the first part of this sequence, Lewis-Williams, also speaks of fragmented consciousness: during the course of any day we are repeatedly shifting from outward-directed to inward-directed states (cf. Lewis-Williams 2002:123). What this means is that sometimes we are fully attentive to our environment, and at other times we withdraw into contemplation and are less alert to our surroundings.