Science and the Inescapability of Metaphysics

The last three centuries have witnessed the great rise of the empirical sciences, such as physics and biology. Indeed, who can deny the extraordinary achievements of science? The technology that we rely on everyday and the life-saving medical procedures that were unavailable to previous times are all the fruit of scientific research. It is so easy to be proud of our scientific achievements that many have come to view science as the pinnacle of human knowledge. In fact, some philosophers and scientists hold that science is the only way to knowledge. This view is sometimes called scientism. Of course, not all philosophers and scientists embrace scientism, but enough do to make it an important issue, well-deserving of our attention.

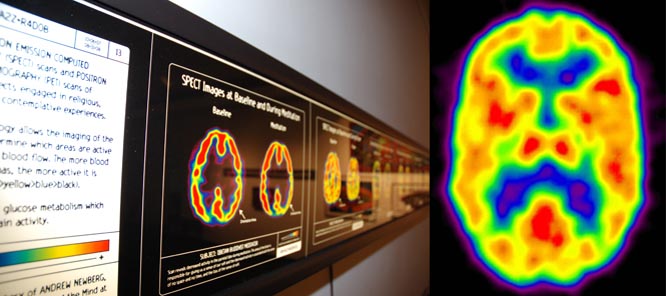

SPECT Images of Brains at Prayer, Courtesy of Andrew Newberg and the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore.

For example, the philosopher Jaegwon Kim has remarked that naturalism is at the heart of much of contemporary analytic philosophy and that the core of naturalism “seems to be something like this: [the] scientific method is the only method for acquiring knowledge or reliable information in all spheres including philosophy.”1 In addition, Mikael Stenmark has noted that many distinguished scientists, who have written best-selling books for general audiences, have embraced scientism.2 For example, Richard C. Lewontin, an evolutionary geneticist, in a review of Carl Sagan’s book, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, wrote, in agreement with Sagan, the following: “to put a correct view of the universe into people’s heads we must … get them to reject irrational and supernatural explanations of the world, … and to accept a social and intellectual apparatus, [namely,] Science, as the only begetter of truth.”3

Obviously, such a position is very controversial. If it is true that science is the only begetter of truth then disciplines such as philosophy and theology must either be absorbed into science, and thereby undergo significant changes, or be denied the status of knowledge. However, if scientism is false then the situation will be quite different. Clearly, much is at stake. In this essay, I argue that scientism is mistaken because science presupposes non-scientific knowledge. In addition, I argue that some of this non-scientific knowledge must be metaphysical. The resulting conclusion is that science cannot escape metaphysics. For this reason, I also argue that scientists and metaphysicians should engage in interdisciplinary work. Before I can make any of these arguments, however, I must clarify my general understanding of metaphysics, which I shall do next.

Different Conceptions of Metaphysics

Philosophers have put forth and attacked many different conceptions of metaphysics throughout the history of philosophy.4 Indeed, metaphysics has been shrouded in controversy for over two thousand years ever since Aristotle tried to distinguish it from other disciplines of learning. Aristotle, I should note, did not use the word ‘metaphysics,’ but instead used several different names for the discipline, including ‘Wisdom’ and ‘First philosophy.’5 In addition, he was rather unclear when discussing what metaphysics studied, and this has led to much disagreement among scholars over how to interpret him. For example, in different passages he says that metaphysics studies substance, first principles and causes, Divinity, being qua being, the attributes of being qua being, and, in one passage, he even says it studies everything.6

Aristotle was clear, however, that metaphysics is the highest of the three theoretical sciences, which included physics and mathematics. Whereas he tells us that these other sciences “cut off a part of being and investigate the attribute of this part,” metaphysics, according to Aristotle, “treats universally of being as being.”7 From these passages, we get a sense that metaphysics is the investigation of the ultimate nature of reality. As such, the questions raised by metaphysics seem to be the most fundamental questions that can be asked. Although there is much that is good in Aristotle’s conception of metaphysics, it is not without some serious problems, and, thus, I will not defend it here.8

Instead, I will defend a different conception of metaphysics, one that appropriates what is good in Aristotle and other metaphysicians, namely, the conception of metaphysics put forth by the philosopher Jorge J. E. Gracia in his book Metaphysics and its Task: The Search for the Categorial Foundation of Knowledge.9 In that work, Gracia argues that metaphysics is the study of categories and it has several tasks.10 With respect to the most general categories, metaphysics aims to identify them, to define them if possible, and to determine the relationships among these categories. With respect to the less general categories, metaphysics aims to fit them correctly into the most general categories, and to determine how they are related to all of the most general categories, including categories into which they do not fit.

To understand what he means by ‘category’ it is important to note two things. First, categories are not predicates. For Gracia, predicability is exclusively the property of words. To predicate is to join words to other words in a certain way.11 In contrast, categories are what the predicable words express. Second, when he says that categories are what the predicable words express, he is using ‘express’ in a technical sense.12 Some words express extra-mental entities, other words express concepts, and still other words express words. According to Gracia, “Each category, qua category, should be considered to be whatever it is, as determined by its proper definition and nothing more.”13

For example, if I say ‘The Triceratops is a dinosaur that existed during the Late Cretaceous Period’ the predicable word ‘Triceratops’ expresses something extra-mental. However, if I say ‘A dream is a mental entity’ the predicable word ‘dream’ expresses something that exists in a mind. Likewise, if I say ‘Preposition is a word’ the predicable word ‘preposition’ expresses a linguistic entity. Finally, if we cannot express something by a predicable word, then it is not a category. Individual entities, such as Plato and Plato’s knowledge of grammar, are not categories because they cannot be predicated. Instead, they function as words of an identity sentence, such as ‘This is Plato,’ and, therefore, are not categories.

Although Gracia’s usage of ‘category’ and ‘express’ is not standard it has several advantages. One advantage is that it allows him to talk about categories in a neutral way that avoids reducing all categories to words, or concepts, or extra-mental entities. This allows him to define metaphysics as the study of categories without reducing metaphysics to realism, conceptualism, or nominalism. Still, Gracia’s view of metaphysics is a kind of realism because he holds that at least some categories are more than words or concepts. Another advantage of Gracia’s view of metaphysics is that it is flexible enough to appropriate insights from other conceptions of metaphysics. As Gracia says:

If my understanding of metaphysics is adopted, the decision as to the ultimate nature of reality will depend on the detailed analysis of particular categories, and especially those which are studied under [the branch of metaphysics known as] ontology. Only then can we expect to come up with a respectable theory. It is not in the definition of metaphysics that this work is to be done, but in the discussion of particular categories.14

Having clarified Gracia’s conception of metaphysics enough for our present purposes, we can proceed to argue for the conclusion that science cannot escape metaphysics. As I mentioned above, the first step towards this conclusion is to argue that scientism is mistaken because science presupposes non-scientific knowledge. However, such an argument requires that we examine scientism and the reasons why it is mistaken more closely. Let us, then, turn to that task now.

Scientism and its Problems

Stenmark has identified many different kinds of scientism, including epistemic scientism, ontological scientism, axiological scientism, and existential scientism.15

To discuss all of these in the depth that they deserve would require more space than I have here. Therefore, I will only focus on the first two because they are, arguably, the most important and common kinds of scientism.

We begin with epistemic scientism, which is the view that “the only reality that we can know anything about is the one science has access to.”16 This kind of scientism tries to reduce all knowledge to scientific knowledge. Under this view, as I mentioned earlier, other disciplines, such as philosophy and theology, must either be absorbed into science, and thereby undergo significant changes, or be denied the status of knowledge. The biologist Edward O. Wilson, for example, seems to espouse such a view in his book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge.17

Although epistemic scientism puts limits on human knowledge, it leaves open the possibility that some realities exist that science cannot discover, such as God. In contrast, ontological scientism puts limits on what exists objectively because it holds that “the only reality that exists is the one science has access to.”18 As Stenmark notes, Sagan’s famous remark that “the Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be” is an example of ontological scientism. The reason is that in order to make such a claim, a scientist like Sagan must hold that science gives us complete knowledge of reality. If science does not give us complete knowledge of reality, or if we are unsure that it does, then we are not warranted in drawing a conclusion like that of Sagan’s above.

This last point raises some doubts about ontological scientism. Do we know for certain, that science does or can give us complete knowledge of reality? Or is this merely an assumption? If it is an assumption then, obviously, there is no guarantee that it is true. And if it is claimed that it is not an assumption, then it must be knowable by scientific means since ontological scientism entails epistemic scientism. Unfortunately, for proponents of ontological scientism, it does not seem possible to determine through scientific experiment that the scientific method can give us complete knowledge of reality. Stenmark discusses the problem in detail:

[H]ow do you set up a scientific experiment to demonstrate that science or a particular scientific method gives an exhaustive account of reality? I cannot see how this could be done in a non-question begging way. What we want to know is whether science sets the limits for reality. The problem is that since we can only obtain knowledge about reality by means of scientific methods … we must use those methods whose scope is in question to determine the scope of these very same methods. If we used non-scientific methods we could never come to know the answer to our question … We are therefore forced to admit either that we cannot avoid arguing in a circle or that the acceptance of [ontological scientism] … is a matter of superstition or blind faith.19

These are mortal blows to ontological scientism. Ironically, ontological scientism itself has turned out not to be a scientific view. And views that assume ontological scientism, such as Sagan’s view of reality, are also not scientific views. Instead, they are metaphysical views that may or may not be true. Since the scientific method cannot be used to determine whether or not such views are true, another non-scientific discipline, namely metaphysics, would have to make the attempt. However, this is only possible if one opts to reject both ontological and epistemic scientism. Epistemic scientism must be rejected since it denies that status of knowledge to metaphysics. Still, there is another option. Scientists can reject both ontological scientism and metaphysics, while continuing to accept epistemic scientism. Of course, scientists who take this option must refrain, unlike Sagan, from taking any metaphysical positions. But this raises another question, namely, is the retreat into epistemic scientism defensible?

Stenmark gives two reasons why the answer is “no.” First, he argues that epistemic scientism is self-refuting.20 This is because, once again, we cannot use scientific experimentation to know that “the only reality that we can know anything about is the one science has access to.” As such, epistemic scientism collapses under its own weight. Second, Stenmark notes that if we are able to know some things independently of science then epistemic scientism is falsified. He gives detailed arguments, which I cannot reproduce here, that there are indeed things we know apart from science. These include memory, observational knowledge, introspective knowledge, linguistic knowledge, and intentional knowledge.21 Moreover, he argues that the activity of science itself presupposes these more basic kinds of knowledge.22

While Stenmark’s arguments above are enough to undermine epistemic scientism, I want to make the additional argument that science cannot escape metaphysics. I believe the key to such argumentation can be found in the fact that science itself presupposes metaphysical knowledge and metaphysical views that are not reducible to science. Let us, then, examine some of these presuppositions.

Metaphysical Presuppositions of Science

One reason why scientists cannot escape metaphysics is because the activity of science itself presupposes some metaphysical concepts and principles. As the philosopher of science Del Ratzsch explains:

One simply cannot do significant science without presuppositions concerning, for example, what types of concepts are rationally legitimate, what evaluative criteria theories must answer to, and what resolution procedures are justifiable when those criteria conflict, as well as answers to deeper questions concerning aspects of the character of reality itself, concerning the nature and earmarks of truth and of knowledge, concerning what science is about and what it is for, concerning human sensory and cognitive and reasoning capabilities, and other matters … Science cannot be done without a substantial fund of nonempirical principles and presuppositions.23

Ratzsch argues that some of the metaphysical principles that scientists adopt are empirically at risk, and therefore they can be rejected given certain discoveries. For example, he discusses how the philosophical principle that natural explanations must be deterministic was ultimately rejected due to the discovery of quantum physics.24 I agree with Ratzsch on this point. However, I would add that there are at least some metaphysical principles and concepts that are necessary presuppositions of science and therefore they cannot be rejected unless one is willing to reject science itself.

In making this claim, I should note that I am presupposing a realistic conception of science, namely, the view that the aim of science is to discover objective truths about reality, where reality is understood as that which exists independently of our minds.25 As examples of such necessary presuppositions of science, I would offer the principle of non-contradiction and the concept of truth, which we shall examine next.

For Aristotle, the principle of non-contradiction is ultimately a metaphysical principle, which he formulates as follows: “[I]t is impossible for anything at the same time to be and not to be.”26 If scientists hold that the metaphysical principle of non-contradiction is false, then we are led to absurdity. This is because a denial of non-contradiction means that it is possible for anything at the same time to be and not to be. So, for example, the planet earth can be both 10,000 years old and 4.5 billion years old at the same time for the same observer. Under these conditions, reality itself is so bizarre that I would argue that it is no longer capable of being investigated scientifically.

To demonstrate this, consider another metaphysical concept that is presupposed by science, namely, truth. If truth is the conformity of a proposition with reality and reality itself exists in a contradictory way then there will be double truths. For example, if the planet earth can be both 10,000 years old and 4.5 billion years old at the same time then it will be true that the planet earth is 10,000 years old and it will also be true that the earth is 4.5 billion years old. Of course, we could deny that truth is the conformity of a proposition with reality but that, it seems, would lead us to some kind of relativism.

The Inescapability of Metaphysics

As the above makes clear, the activity of science, at least when it is understood in a realist way, presupposes a certain framework. And elements of this framework such as the principle of non-contradiction and the concept of truth cannot be investigated or justified through the scientific method. As such, they will have to investigated and justified in another discipline, namely philosophy, and, more specifically, metaphysics. This justification is necessary to the extent that scientists want to hold that their theories are true, or at least approximately true, and in order to respond to the postmodernist attacks on science that have challenged its status as knowledge.

Metaphysics is inescapable, then, because a realist conception of science requires a philosophical foundation, part of which must be metaphysical. And this inescapability becomes even clearer if we adopt Gracia’s understanding of metaphysics. This is because the categories of science are related to the most general categories of metaphysics, and therefore any scientific view is incomplete until these relations are clarified. It is metaphysics, as Gracia explains, that provides the categorial foundation of all knowledge, including the sciences:

Metaphysics, then, turns out to be the categorial foundation of knowledge. For in it we attempt to establish and understand the most general categories and the relation of all other categories to them. … As the view of these categories and their relations, metaphysics is logically presupposed by every other view that one may have. Any account of what we know or think we know, then, is incomplete until we provide its metaphysical foundation. We can, of course, practice other disciplines and hold other views without consciously practicing metaphysics or holding metaphysical views, but in these cases we do in fact vicariously engage in metaphysics and hold metaphysical views, for the views we hold logically presuppose views about the most general categories, their interrelations, and the relation of the less general categories we use to the most general categories. All our knowledge depends on metaphysical views whether we are aware of it or not, and all our thinking involves metaphysical thinking. Those who delude themselves in believing that they do not engage in metaphysical thinking nonetheless do. The only difference between them and declared metaphysicians is that the former are unaware of what they do and, therefore, do it surreptitiously and unreflectively, whereas the latter are aware of it and do it openly and deliberately. Metaphysics is inescapable.27

Because metaphysics is inescapable, scientists and metaphysicians should engage in interdisciplinary work. But in order for that to happen the current climate must change. Albert Einstein once wrote, when commenting on the work of Bertrand Russell, that he lamented the “fear of metaphysics” that many thinkers have inherited from David Hume.28 Fear, however, should not keep scientists and metaphysicians apart, especially given the great cosmological and biological discoveries of the last few decades. Now is the time for greater dialogue and greater interdisciplinary work.29

References

1 Jaegwon Kim, “The American Origins of Philosophical Naturalism,” Journal of Philosophical Research, the APA Centennial Volume, 2003), p. 87.

3 Richard C. Lewontin, “Billions and Billions of Demons,” The New York Review, January 9, 1997, p. 28.

4 See Jorge J. E. Gracia, Metaphysics and its Task: The Search for the Categorial Foundation of Knowledge (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1999), pp. ix-xiii; passim.

7 Ibid., 1003a23-25, trans. W. D. Ross, The Basic Works of Aristotle, ed. Richard McKeon (New York: Random House, 1941), p. 731.

8 For example, Gracia argues there are some serious problems with the view that metaphysics studies being qua being. See Gracia, Metaphysics and its Task, pp. 25-28.

23 Del Ratzsch, Nature, Design, and Science: The Status of Design in Natural Science (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2001), p. 82.

25 Realism in one form or another has been the dominant view of science for most of history and it is currently the dominant view among philosophers of science. See Frederick Suppe, The Structure of Scientific Theories (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2nd ed., 1977), pp. 652, 716-728.