H-: Brains, Selves and Spirituality in the History of Cybernetics

This essay is a revised version of a paper presented at the Max Planck Institute for History of Science, Berlin,

I

I was pleased to be invited to this meeting—I knew almost nothing about transhumanism when I got the invitation, and thinking about it seemed like an interesting challenge. I had intended to write a paper just for the meeting, somehow the time evaporated (my return to England) so I sent along a recent paper deriving from my research into the history of cybernetics that touches on some relevant issues, I think, and in these remarks I’ll try to join up a few dots.

First remark: if transhumanism didn’t exist it would be necessary to invent it. The aspiration to transcend the human form does a wonderful job in inviting the numinous question: what does it mean to be human? Or as Don Ihde put it, “of which human are we trans?” So that is the question that I want to dwell on—what does it mean to be human? And the best way I’ve found to proceed is to contrast the answer that I’m inclined to give, based on my analyses of scientific practice and my more recent work on the history of cybernetics, with the answer offered by the transhumanists. Immediately we run into a problem—I think the transhumanists might not have a single agreed position. So for the purpose of exposition I’ll narrow my definition of transhumanism down to the goal of ‘cybernetic immortality’ as a sort of defining outer limit of transhumanist thought.

So, what is cybernetic immortality? I take it be the idea that we can achieve a sort of immortality by downloading (or uploading) our consciousness into a computer (and then it can move around from machine to machine forever). What can we say about this idea? First, it exemplifies the transhuman aspiration very nicely—it envisages shuffling off the material form of the human body entirely. Second, it answers the question “what does it mean to be human” very clearly. A certain timeless essence of humanity—consciousness, the mind—is to achieve immortality, with all the useless paraphernalia of humanity—the body, even the unconscious and subconscious reaches of the mind—to be sloughed off.

How might we react to this version of what it means to be human? We could start by noting that there is something very odd about it. Its vision of the human essence is actually a historical construction, invented by the Enlightenment. Of course, you might like the Enlightenment and you might want to make its privileging of the mind and reason a permanent feature of humanity, as in cybernetic immortality. However, it’s worth noting that what is envisaged here is a freezing and a narrowing of the human form—the imposition of a historically specific definition rather than the liberation of an eternal essence. Actually, it’s this impulse towards freezing that worries me most about transhumanism.

As I move towards my own work, a few more thoughts spring to mind. In my book The Mangle of Practice: Time, Agency, and Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995) I was led to emphasize two aspects of being in the world: what I called a posthumanist entanglement of the human and the nonhuman, and temporal emergence: the continual bubbling up of irreducible novelty in the world. My sense of ‘posthumanism’ is thus more or less the inverse of how the same word is used in connection with transhumanism. The latter refers to a splitting off of consciousness from materiality, whereas I want to argue for a decentered analysis that foregounds the constitutive coupling of consciousness, reason, the self, etc with the material world. Where does this divergence leave us? I’m inclined to stick to my story, but that doesn’t mean I have to regard cybernetic immortality as a totally mistaken idea. Presumably even downloaded consciousnesses would have something to interact with—the material world via some sort of motor organs, or just each other—so, oddly, a decentered posthumanist analysis, in my sense, would still go through. These disembodied consciousnesses would still be constitutively plugged into the world as we are, but differently—not through the medium of the fleshly body.

This, of course, raises the question of whether the medium of being matters. And this, in turn, is the sort of question that phenomenologists like to meditate on, so maybe I should leave it for Don Ihde to answer. However for myself, I have to say that, as mentioned in my paper, I’m taken by a very literal understanding of Michel Foucault’s notion of technologies of the self. Different technologies, different material set-ups, indeed elicit different inner states. And I’m willing to bet that cybernetic immortality would entail some sort of technologies of the self, and that the selves they elicit would be very different from the selves we have today. And the moral of this is that even if transhumanists aim at the simple liberation of some timeless human essence, they would end up with something they did not expect—which again problematizes their version of what it means to be human. And, of course, we could have reached the same conclusion by thinking about emergence—we have to expect new selves to be continually bubbling up in our dealings with the material world, even dealings that aim to hold the self constant.

I should think more now about this phrase, ‘cybernetic immortality,’ and I want to make a distinction concerning the referent of ‘cybernetic.’ The sense invoked by the transhumanists appeals to the information-theory branch of cybernetics, and more broadly to anything to do with AI and computers. This hangs together perfectly with the Enlightenment image of reason as the human essence. However, in The Mangle I argued that we can’t get to grips even with Enlightenment science itself by focusing on reason alone. Instead we need to begin with performance—the idea that we humans are linked into the world via dances of agency, coupling our performances with those of the world. This emphasis on performance is a very different answer to the question of what it means to be human than the Enlightenment’s, and, as it happens, there is a very different branch of cybernetics that stages and acts out this vision for us, the branch that flourished in Britain after the war, and that I talk about in my paper. And one interesting aspect of this difference is that it invites very different fantasies of immortality from Enlightenment cybernetics.

This revolves around the biological computers that I mentioned in my paper below—meaning naturally occurring adaptive systems enrolled into human projects as performative brains. Stafford Beer and Gordon Pask imagined these as substitutes for human factory managers, and went so far as to devise ways to train them to function as such. The basic idea was that the human manager would monitor the performance of the adaptive system and somehow reinforce moves that he or she approved of, until the system achieved a level of performance that the human could live with—at which point the human could withdraw and leave the factory to be managed by a pond or some electrochemical threads or whatever.

The simple point I want to make here is that after training one can regard the computer as a sort of model of the human manager, inheriting his or her performative competence—and I cannot see why one should not think of this as a species of genuinely cybernetic immortality: the key competence of the human would here be indeed downloaded, not into a digital machine but into some lively and adaptive nonhuman material. However, something very different from consciousness gets downloaded here, into a medium very different from a digital computer. Hence, we can see that very different modes of immortality are imaginable depending on what one thinks it means to be human. To put it another way, we can see more concretely through this example how current discussions of cybernetic immortality amount to a freezing and narrowing of the space of future possibilities. I would hate to see the Enlightenment story of humanity made irrevocably true by biotech and AI.

I could say some more about my cyberneticians. If I wanted to persuade you to take them seriously, I would go on about their work in robotics, complex systems theory, management and so on—nice down to earth topics that Enlightenment thinkers can recognize—but one thing that interests me a lot about them is precisely that they had some unconventional ideas about the self, as discussed at some length in my paper. These follow immediately from the notion of the brain and the self as performative. The Enlightenment self is given and conscious—it’s the kind of self that does IQ tests and that AI models—which is why academics can mistake it for an essence. The performative self, in contrast, is opaque to consciousness, the sort of thing one can find out about experimentally. And in my paper I show how in the history of cybernetics this sort of curiosity about the performative self has been entangled with all sorts of technologies of the self (including flickering strobe lights and hallucinogens, as well as meditation), and with associated altered states, explorations of consciousness, strange performances, magic, the siddhis, the decentered dissolution of the self, tantric yoga and union with the divine. The self, as revealed here, turns out to be inexhaustibly emergent, just like the world—the antithesis of the given human essence of the Enlightenment and cybernetic immortality. And again, for me, this shows the extent of the freezing and narrowing of the human that transhumanism entails—the severity of its editing of what the human might be. Of course, all of the practices and states that I talk about in my paper are already marginalized in contemporary society—it feels vaguely embarrassing to talk about them in public. But at least the margins exist, and one can go there if one likes. The transhumanists would like to engineer them out of existence entirely and forever. Yes, I’m starting not to like transhumanism.

As an aside here I could state the obvious: that cybernetic investigations of the self lead straight into the space of the spiritual, though the immediate resonances and affiliations are with Eastern spirituality rather than Christianity. There is, of course, an important and distinctly Christian line of the critique of transhumanism that emphasizes a deep significance of death and resurrection that transhumanism skates over. However, it is worth emphasizing a certain isomorphism here of critique and criticized: both positions assume that they already know substantively what it means to be human. Both would like to freeze the human in place; neither acknowledges a significant space for emergence. From this spiritual angle, then, the mangle, cybernetics and Eastern spirituality all serve to thematize the narrowness of current debates both for and against transhumanism. “Who knows what a body can do?”—do we want to foreclose this question?

Let me come at this topic from one last angle. Transhumanism has a telos: it thinks it can see the future and how to mobilize science and technology to get there. Clearly the mangle and cybernetics contest this idea. But I find it interesting to confront it historically, too. In a paper available on the web (‘Facing the Challenges of Transhumanism: Philosophical, Religious, and Ethical Considerations’), Hava Tirosh-Samuelson credits the word ‘transhumanism’ to Julian Huxley in 1957, but traces the origins of the idea back to the 1920s and 1930s in the writings of J.B.S. Haldane, J.D. Bernal and Julian’s brother, Aldous Huxley. I would be interested to know more about Haldane’s and Bernal’s thinking in this area, but I know something about Aldous and Julian Huxley from my work on cybernetics and the 1960s. Their writings are, for example, central to the present-day human potential movement, which focuses on precisely the sort of altered states and strange performances that I just mentioned as edited out of the transhumanist vision. The canonical recent text here would be Michael Murphy’s enormous 1992 book, The Future of the Body: Explorations into the Further Evolution of Human Nature.

So there is a continuing, if marginal, tradition here of imagining an emergent rather than essentialized answer to the question of what it means to be human. It interests me that also back in the 1920s and 1930s one can find important works of fiction that point in the same direction. A couple of weeks ago I happened to read a canonical fantasy novel from the period, David Lindsay’s Voyage to Arcturus, and in it Lindsay elaborates the idea of an unstable material and physical environment in which humanity continually develops entirely new limbs and sense organs. I also think of Olaf Stapledon’s 1931 novel, Last and First Men. This sketches out an imaginary longue durÈe history of the future of the human race stretching over millions of years, in which humanity eventually seizes control of its own evolution, as the transhumanists would say. However, instead of freezing our form in the name of transhumanist perfection, we experiment with it. In the chapter that I remember best, the human race acquires wings and takes to the air, and Stapledon elaborates the posthumanist (in my sense) point brilliantly by conjuring up the changes in subjectivities and social relations that go along with the new aerial existence—flight as a technology of the self, producing a new kind of people.

Why do I mention this now? For three reasons: First, because Last and First Men is a very nice example of the sort of vision of the future that might go with the mangle and cybernetics—a vision of open-ended experimentation, emergence and transformation with no fixed end. Second, because an interesting project in the history of ideas comes into sight here. I would like to know how it came to be that in the 20s and 30s people were able to imagine radical transformations of the human form, when no evident technological possibilities were at hand. And third, from the opposite angle, I am struck by the impoverishment of our imagination that has since come to pass. Now we have biotechnology, now we really could dream of equipping ourselves with wings or new senses, but we don’t. Instead of experimentation with the endless possibilities of humanity, we dream transhumanist dreams of purification and the excision of what already exists, of downloading consciousness. Something profoundly sad has happened to our imagination. That, in the end, is what transhumanism brings home to me.1

II

My research in the history of cybernetics in Britain has taken me to strange and unexpected places. Grey Walter’s 1953 popular book, The Living Brain, is, on the one hand, a down-to-earth, materialist and evolutionary story of how the brain functions. I know how to deal with that. However, it is also full of references to dreams, visions, ESP, nirvana and the magical powers of the Eastern yogi, such as suspending the breath and the heartbeat—siddhis as they are called. I never knew what to make of this, except to note how strange it is and that respectable scientists don’t write about such things now. But then I realized that I should pay attention to it. Walter was by no means alone on the wild side. All of the other cyberneticians were there with him. In his private notebooks Ross Ashby, the other great first-generation cybernetician in Britain, announced that intellectual honesty required him to be a spiritualist, that he despised the Christian image of God and that instead he had become a ‘time worshipper.’ Gordon Pask wrote supernatural detective stories. Stafford Beer was deeply absorbed by mystical number-systems and geometries, happily sketched out his version of the great chain of being, taught Tantric yoga and attributed magical powers like levitation to his fictional alter ego, the Wizard Prang. Echoing Aldous Huxley on mescaline, Gregory Bateson and R D Laing triangulated between Zen enlightenment, madness and ecstasy.

Strange and wonderful, surprising stuff. What is going on here? I want to try to sort this out, and tie it back to a distinctive conception of the human brain.2

Meditating on the history of cybernetics has helped me see just how deeply modern thought is enmeshed in an endlessly repetitive discourse on how special we are, how different human beings are from animals and brute matter. It is, of course, traditional to blame Descartes for this human exceptionalism, as we might call it.3 However, while we may no longer believe we have immortal and immaterial souls, the human sciences seem always to have been predicated on some immaterial equivalent that sets us apart: language, reason, emotions, culture, the social, the dreaded knowledge or information society in which are now said to live. This sort of master-narrative is so pervasive and taken for granted that it is hard to see, let alone to shake off and imagine our way out of. This is why we might learn from cybernetics. It stages a non-dualist vision of brains, selves and the world that might help us put the dualist human and physical sciences in their place and, more importantly, to see ourselves differently and to act differently. Let me talk about how this goes.

We should start with the brain. The modern brain, as staged since the 1950s by AI for example, is cognitive, representational, deliberative—the locus of a certain version of human specialness. The key point to grasp is that the cybernetic brain was not like that. It was just another organ of the body, an organ that happens to be especially engaged with bodily performance in the world. In this sense, the human brain is no different from the animal brain except in mundane specifics: Ashby, for example, noted that we have more neurons and more neuronal interconnections than other species, making possible more nuanced forms of adaptation to the environment. And, of course, the defining activity of first-generation cybernetics was building little electromechanical models of the performative brain—Walter’s tortoises and Ashby’s homeostats—thus completing the effacement of difference between humans on the one side and animals, machines and brute matter on the other. This is what I like about cybernetics: it was and is nowhere in the Cartesian space of human exceptionalism. It reminds us that we are performative stuff in a performative world—and then elaborates fascinatingly on that. Now I want to try to make sense of some of these elaborations as they bear on non-Cartesian understandings of minds, selves and spirit.

pictures: tortoise & homeostat

Altered States and Strange Performances

The Cartesian brain is available for introspection. We know our own special cognitive powers and feelings, and it is the job of AI, say, to reproduce those powers in a computer program. However, the performative brain is not like that. Walter’s tortoises navigated their environments without representing them at all. In general, cybernetics understood performance as largely happening below the level of consciousness and as thus unavailable to inspection. Ashby’s model for the performative brain was bodily processes of homeostasis—keeping the blood temperature constant—something that all mammals do, but not by thinking about it. This unavailability of the performative brain at once made it an object of curiosity—who knows what a performative brain can do? This simple curiosity in turn explains much, though by no means all, of the cyberneticians’ travels in forbidden lands. If mainstream Western culture defines itself by a rejection of strange performances, well then, other cultures can be seen as a repository of possibilities, hence Walter’s interest in nirvana and the yogic siddhis. He was happy to recognise that Eastern yogis have strange powers; he just wanted to give a naturalistic explanation of them in terms of the performative brain. The siddhis were thus, according to Walter, instances of disciplined conscious control of otherwise autonomic bodily functions; nirvana was the absence of thought in the achievement of perfect homeostasis—the disappearance of the last relic of the Cartesian mind. Beer thought differently. He practiced yoga; the siddhis were real to him, the incidental powers that arise on a spiritual journey. We can come back to spiritual matters in a minute.

With the exception of Beer, siddhis and the like were matters of distant report to the cyberneticians, not personal experience, and another hallmark of early cybernetics was the pursuit of parallel phenomena that were accessible to Western means of investigation, hence the interest in ESP-phenomena. Hence, several of my cyberneticians belonged to the British Society for Psychical Research, as I recently found out. However, the key discovery in this respect was undoubtedly Walter’s of flicker. In the course of EEG research in 1945, Walter and his colleagues discovered that gazing with eyes closed at a strobe light flickering near the alpha frequency of the brain induced visions: moving, coloured patterns, often geometrical ones but also visions of events like waking dreams. This flicker experience was important to the cyberneticians and psychical researchers precisely as a vindication of an understanding of the brain as performative and endlessly explorable rather than cognitive and immediately available. So a couple of comments are appropriate here.

First, flicker vividly problematised any notion of the brain as an organ of representation. One indeed sees strange and beautiful patterns in a flicker set-up, but the patterns are equally obviously not there in the world. The strobe just flashes on and off, but the patterns move and spiral through space. Second, flicker thematizes a non-dualist coupling of the brain to the world. The brain does not choose to see moving patterns; the external environment elicits this behavior from the brain. To see what is going on here, I can’t help thinking of Michel Foucault’s idea of technologies of the self. In Foucault’s own work, these are technologies that produce a distinctly human, self-controlled self—the kind of self that sets us apart from animals and things. Flicker, then, is a different kind of non-modern, non-Cartesian technology of self—a technology for losing control and going to unintended places, for experiment in a performative sense. Much of the literature in this area can be read as devoted to strange performances and the technologies of the self that elicit them. Aldous Huxley’s second book on his mescaline experience, Heaven and Hell (1956), is one long catalogue of technologies for eliciting non-modern selves open to mystical experiences, including holding one’s breath, chanting and flagellation as well as psychedelic drugs and, yes, flicker.

What interests me most here, I think, is how drastically these technologies and their associated altered states undercut our notions of the modern self. They remind us that there are other ways to be; other selves that we can inhabit. They show vividly and by contrast, just how straitened the modern self is, and just how constrained the human sciences that celebrate the modern self are.

The Decentered Self

We can think about another aspect of the cybernetic brain. I said that it was performative, and now I need to add that in the main line of cybernetic descent, the brain’s role in performance was that of adaptation. The brain, above all the organs, is what helps us cope with the unknown and get along in a world that can always surprise us in its performance. Adaptation is an interesting concept in the present connection because it is intrinsically relational. One adapts to specific others as they appear, not to the world in general once and for all. This in turn implies a sort of decentring of the self that, again, cybernetic technologies of the self help stage for us. When Allen Ginsberg, the Beat poet, took LSD for the first time it was in conjunction with a feedback-controlled flicker set-up, and he afterwards wrote that he felt that his soul was being sucked away down the wires. So much for Descartes.

We could move in several directions from here. One is into the arts. Gordon Pask constructed an original aesthetic theory based on the idea that human beings actually find pleasure and satisfaction in performative adaptation to others, human or nonhuman. In the early 1950s, his famous Musicolour machine was an instance of this. Musicolour translated a musical performance into a light show, but its defining feature was that its parameters evolved as a function of what had gone before, so that it was impossible to gain a cognitive overview of the linkage between sounds and lights. The performer thus had continually to adapt to the machine just as it adapted to him or her, and the overall performance was a dynamic and decentered joint product of the human and the nonhuman—literally a staging of the relational brain and self, now in the realm of the arts and entertainment. Here I could make two observations: The first is that here we can see clearly that what is at stake is not simply ideas about the brain and the self. Distinct and specific projects and forms of life hang together with these ideas—different ways to live. Again, this observation serves to thematize the straitened character of both the Cartesian self and the human sciences, now aesthetics, that conspire to naturalize these selves. The other observation is that the strangeness of Pask’s work is manifest in the fact that no-one, not even Pask, was sure what a Musicolour machine was. He later wrote of trying ‘to sell it in any possible way: at one extreme as a pure art form, at the other as an attachment for juke boxes.’ Much the same could be said of the Beat writer and artist Brion Gysin’s attempt to market flicker machines as a performative substitute for the living-room TV.

picture: flicker — gysin

Another direction in which we could travel is madness. Madness for the cyberneticians was just another of those altered states the performative brain could get into, as usual elicited by specific technologies of the self. Walter drove his robot tortoises mad by placing them in contradictory set-ups in which their conditioning pointed them to contradictory responses. He also cured them with other set-ups that he analogized to the brutal psychiatry of his day: shock, sleep therapy and lobotomy. Gregory Bateson refined this picture in his story of the double-bind as a contradictory social situation to which the symptoms of schizophrenia were an unfortunate adaptation. Here what interests me most is that at Kingsley Hall in the second half of the 1960s, R D Laing and his colleagues put this decentered and performative image of schizophrenia into practice, in a community in which psychiatrists and the mad (as well as artists and dancers) lived together on a par, rather than in the rigidly hierarchic relations of the traditional mental hospital. Kingsley Hall was another technology of the self—both an antidote to the double bind for sufferers, and, as Laing put it, a place where the mad could teach the sane to go mad—where new kinds of self could emerge. Again, Kingsley Hall makes the point that it is not just ideas that are at stake here, but other forms of life too. And something of the strangeness of this other form of life is caught up by the label anti-psychiatry that attached to the Bateson-Laing enterprise. A style of adaptive architecture, associated with the Archigram group as well as Cedric Price and Gordon Pask, likewise found itself described as anti-architecture. I find these links from the non-Cartesian performative and adaptive brain to these strange forms of life fascinating.

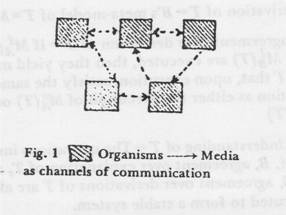

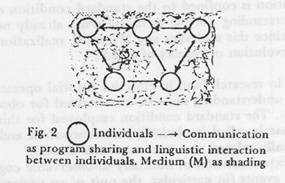

The third axis we can explore under this heading is ‘alternative spiritualities.’ The decentering that goes with the adaptive brain of course pushes us in the direction of Eastern spirituality. Instead of the centered and unchangeable soul one finds a self that evolves and becomes in the thick of things, and this just is a Buddhist analysis of the self. One can plunge into this further. Here is a diagram drawn by Gordon Pask in connection with his work on cybernetic machines for entertainment and education. It is labeled ‘two views of minds and media.’ Both views are decentered, focusing on the relationality of communication. One diagram enshrines a conventional view of this process and shows minds communicating with one another through some medium—words traveling through the air, say. But Pask wrote that ‘I have a hankering’ for the other view, in which minds are somehow ‘embedded’ in an all-pervasive communicational medium.

diagrams: minds and media (1977)

These diagrams seem quite innocuous unless one immerses oneself in the sort of scientific/spiritual literature found in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, when the occult significance of diagram (b) becomes clear. The idea behind diagram (b) is that the brain is the organ of a strange sense, unrecognized in the West, capable of accessing some other, non-human and intrinsically spiritual realm that one may as well call ‘universal mind.’ One finds this idea in Ashby’s notebooks from the early 1930s. In the passage where he admits to himself that he should be a spiritualist, he sketches out precisely the idea of the brain as a sort of hyper-sensitive (by virtue of its material complexity) radio receiver, uniquely open to signals in a spiritual aether. Over the years, one finds this image endlessly elaborated in attempts to understand phenomena like ESP, which become much more plausible if they have their own medium in which to happen, and in the ideas of ‘evolutionary consciousness’ which one finds in important branches of New Age philosophy.

If Pask’s diagram of minds and media remains philosophical and representational, Aldous Huxley made a different connection to the spiritual realm in making sense of his mescaline experience. In the beautiful description of the phenomenology of psychedelic drugs that he gave in The Doors of Perception, Huxley appealed to Buddhist imagery to convey the intensity of his experiences—seeing the Dharma-body of the Buddha in the hedge at the bottom of the garden is the image that sticks in my mind. So here the altered states induced by chemical technologies of the non-modern self are immediately identified with those other altered states induced by Buddhist and more generally mystical technologies of the self. Interestingly, Huxley even offers an explanation of why mystical experiences are so rare in terms of the key concept of cybernetics, adaptation. His famous theory of the brain as a ‘reducing valve’ elaborates the idea that evolutionary processes have set us up to perceive the world in directly functional and performative terms. Mescaline and other technologies of the self then serve to undo this focused and performative stance, at least for a while, allowing us to latch onto the world in other ways.

Finally, I can just note that the references so far to siddhis and strange performances point directly not just to Eastern philosophy but also to Eastern spiritual practices—to non-modern technologies of the self again. If you really want to know about siddhis, a place to start is with Mircea Eliade’s big book, Yoga: Immortality and Freedom (1958). This intensely scholarly tome surveys the history and substance of the whole range of Indian yogic traditions, and singles out tantric yoga as the form that emphasized bodily techniques, altered states and strange performances—the siddhis—as well as magic and alchemy. Stafford Beer, as I said, practised and taught tantric yoga—he lived all this stuff.

In all these ways, then, the adaptive brain of cybernetics extended into a distinctly and integrally spiritualized set of understandings and forms of life, running from psychedelic explorations of consciousness to strange yogic performances. The oddity of it all against the backdrop of, say, mainstream contemporary Christianity, is manifest. Again, we are reminded of the straitened and impoverished conceptions of the self and the spirit that the modern West affords us, and that we act out in our daily lives, and of the complicity of the modern social and human sciences in this narrowing and constriction of thought and action.

Hylozoism

So far I have been dwelling on cybernetics as a science of the performative brain, in contrast to the more familiar cognitive version. Now I should recognize that the cyberneticians did not deny the brain its cognitive capacity. Rather, they wanted to put cognition in its place. Like me in The Mangle of Practice, they argued for a performative epistemology in which knowledge and representation are seen as intimately engaged in performance, as revisable components of performance, having to do with getting along better or worse in the world, rather than as something especially human and having to do with making accurate maps and winning arguments. Beyond that, however, the cybernetic focus on the adaptive brain—the brain that helps us get along with the unknown and unknowable—in turn thematized what one might call the performative excess of the world in relation to our cognitive capacity—precisely the ability of the world always to surprise us with novel behavior.

This explicit recognition of the performative excess of the world feeds into my last topic, which I refer to by the slippery word hylozoism. Hylozoism, for me, refers to a kind of spiritually charged wonder at the performativity and agency of matter, and Stafford Beer was certainly a hylozoist under this definition. He wrote poems on the computational power of the Irish Sea as indefinitely exceeding our own. ‘Nature is (let it be clear that) nature is in charge’ he wrote in 1977. What interests me most, again, is that this hylozoism was not just a philosophical position, an idea of what the world is like. Again, the cyberneticians elaborated it in all sorts of practices, including engineering and the arts.

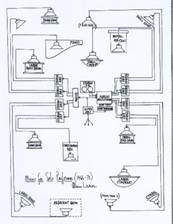

In modern engineering, the dominant approach is a version of what Martin Heidegger called enframing. The world is materially reformed and reconfigured to try to accomplish some preconceived goal according to a preconceived plan. Beer and Pask developed a quite different approach, that one could associate with revealing, not enframing—an open-ended exploratory approach of finding out what the world can offer us. Perhaps the best way to grasp this is via the notion that whatever one wants in the world, it’s already there, somewhere in nature. I think here of the craziest and most visionary project I have ever come across in the history of technology, Beer and Pask’s attempt to construct non-representational biological computers. The idea is simple enough once you see it. Ashby had argued for the idea of the brain as an organ of performative adaptation, and Beer stood this idea on its head: any adaptive system can function as a brain. In the late 1950s and early 1960s Beer and Pask then embarked on a long search through the space of adaptive systems running from pond ecosystems to electrochemically deposited metal threads as some sort of substitute for human factory managers.4 They failed, but the problem lay in getting adaptive systems to care about our projects rather than any difficulties of principle. Once more the contrast between this sort of hylozoist engineering and that taught in engineering schools is manifest; this time we would have to blame the modern natural sciences and IT strategies, rather than the social sciences, for conspiring with the narrowing of our imagination of the world itself against which biological computing stands out.

We can see hylozoist parallels in the arts to this style of cybernetic engineering. Brian Eno said he was indebted to Stafford Beer’s Brain of the Firm for innovative changes in his music in the 1970s. If classical music consists in the reproduction of a pre-conceptualised score, Eno’s generative music consists, as he once put it, in ‘riding the dynamics’ of unpredictable algorithms and finding out what emerges, as if the music was already there, now in the domain of computational systems. In the realm of what used to be called sculpture, Garnet Hertz built a robot very similar to Grey Walter’s tortoises, but with the electronics replaced by an optically and mechanically coupled giant Madagascan cockroach, and exhibited it as an art object.

picture: roach robot

The artist Eduardo Kac has done much the same with bio-robots and genetically modified animals, and Andy Gracie’s artwork explores the dynamic possibilities of interfering with natural processes of growth and adaptation. My favorite example of hylozoist art, however, is biofeedback music. Developed by people like Alvin Lucier, biofeedback music consists in extracting naturally occurring electrical rhythms from the brain and using them to control sound-making equipment. Once more we arrive at the hylozoist idea that it’s all already there in nature; there is no need for that long trip through the centuries of compositional development in the history of the West—all you need is a few electrodes and wires. And yet again, the strangeness of this sort of performance is evident. As James Tenney (1995, 12) put it: ‘Before [the first performance of Lucier’s Music for a Solo Performer] no one would have thought it necessary to define the word “music” in a way which allowed for such a manifestation; afterwards some definition could not be avoided.’

pictures: music for solo performer; john cage & biofeedback

It is also worth noting that biofeedback is historically related to Grey Walter’s EEG research, and originated as a technique for interfering with one’s own brainwaves. It was taken up in the 60s as a technique for achieving the same sort of transcendental inner states as meditation and psychedelic drugs, and performances of biofeedback music often entailed the achievement of such altered states by performers (individually or collectively) and the audience. So this new sort of music was directly performative as itself a technology of the self for achieving altered states and non-modern subject-positions.5

To wrap things up, I want to say that in elaborating a conception of the brain as adaptive and performative, the history of cybernetics dramatizes visions of the self and spirituality and the arts and engineering and the world, that go far beyond those prevalent in contemporary society and the mainstream sciences, and that cybernetics acted out those visions in all sorts of strange, surprising and wonderful projects. As I have said several times, I take it that this sort of ontological theatre points up the narrowness of our hegemonic forms of life and the role of the natural as well as the social sciences in closing down our imagination and naturalizing this constriction.

Endnotes

2 A much fuller treatment of the topics to follow (and much else) complete with citations to sources is to be found in my forthcoming book: Sketches of Another Future: The Cybernetic Brain, 1940-2000 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

3 The canonical transhumanist dream of downloading consciousness to a computer is, of course, a species of human exceptionalism writ very large. My idea here is to explore a different mode of being in the world and where it might lead us, especially across spiritual terrain.

4 There is a close resemblance between this idea of substituting biological computers for human managers and the transhumanist project of downloading human consciousness into a digital computer. The axis of differentiation, besides the very different substrates involved, is that what gains ‘cybernetic immortality’ in biological computing is not the conscious, reasoning brain of the manager but his or her preconscious, performative and adaptive capabilities.

5 There are many threads that one could follow in exploring the theme of hylozoism in the arts and science including the role of the camera obscura in the extreme realism of Vermeer’s paintings (which apparently include reflections of the camera itself); Bernard Palissy’s amazing techniques for turning living creatures into pottery; Pamela Smith’s writings, which suggest that much of what is usually taken to be alchemical symbolism is actually a literal description of the mediaeval vermilion synthesis; Galison’s account of the history of the bubble chamber, with C T R Wilson trying to create real meteorological phenomena in his early cloud chambers; and D’Arcy Thompson on the 19th-century science of inkdrops.